A showcase day of unionist culture was held at 2 Royal Avenue, Belfast, with activities of a cultural identity video; a “living library” event; a talk by historian and broadcaster, Dr David Hume; an exhibition of archival footage by NI Screen of cultural events; and music performances.

The event was organised by Belfast City Council, through its Good Relations Action Plan, Cultural Inclusion and Co-Design. This programme has been running since June 2022, with participants engaged in a process to develop and consider a range of supports, projects, and ideas that could assist the broad unionist community in developing capacity and leadership in relation to cultural expression.

Dr David Hume

Dr David Hume began with a recollection of a visit to Lincoln County, Georgia, where he met actors who performed re-enactments of the American civil war, including one who played a tune on his guitar that Hume recognised “as living history” from the Williamite wars — explaining how folk in the Appalachian mountains were known as “King Billy’s men” hence the nickname of “hillbillies”:

“For me, this was all about history coming to life, in terms of the culture that people had taken across as people that we would equate with the PUL [Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist] community in general today.”

Hume asked what things define the PUL community, and began with “origins”:

“In my own case, I have links with the Scottish borders, and I’m always conscious where I grew up we could see Scotland twenty minutes away… across the channel are the hills of Galloway… we’re as close to Galloway as we are to Belfast in our part of the world.”

He said that the consequential connection between those two areas over the centuries is very strong, referencing people who came over from the Scottish Lowlands and borders region, as well as parts of England: “Origins are important because they helped to provide the DNA of who people are and what their culture is.”

Hume described the land and people who lived in the border region, and described them as not having a great deference to authority, quoting Thomas Musgrave: “These people are Scottish when then will and English at their pleasure.” As Hume put it, “They’re nobody’s man, they look after themselves, and they have their own, very strong, clan system… That says quite a bit to me about the psyche of the PUL community and Ulster-Scots particularly.” He further explained that a lot of these border people came across as the Ulster plantation and also onto America’s frontier: “They always ended up on frontiers because they were frontier people.”

Military-style parading went back to the Irish volunteers in the 18th century, Hume explained. Marching bands are a part of the parading tradition, Hume continued, with now some very large bands and associated costs of uniforms and instruments, often competing with each other: “There’s a very strong sense of community within bands because they are literally banded together.” He also complimented the tuition and accomplishment of musical abilities within the bands.

In the phrase, “PUL community”, “’P’ stands for Protestant,” Hume highlighted, “not as one common block”, but with differentiation from the English and Scottish reformations. As he explained, the former kept much of the hierarchy of the Catholic church, replacing the head with King Henry VIII, while the Scottish church system changed from the ground up, with presbyteries electing individual church moderators and the Presbyterian church overall: “This flows out of the Reformation ideas at the time and also flows into society, particularly in the case of Presbyterians, or the Ulster-Scots as we call them as well.”

Hume presented some symbolic examples, such as bands called “The Protestant Boys” and banners with images of the Bible and royal crown. Interestingly, he suggested that like a secularisation of the Jewish community in America, people in the PUL community could be “culturally Protestant” but not necessarily “religiously Protestant”: “They’re not going to be at church every Sunday, but they still identify themselves as part of that Protestant culture and identity.”

Another item that Hume argued was associated with the PUL community was a sense of military service. He told a story of one of his relations, from Ballyboley, County Antrim, who signed up with the Scottish Guards, served in Argentina, then signed up upon return to Liverpool in 1914. Unfortunately, this soldier was killed at the Battle of the Somme, which Hume described as part of the iconography within the PUL community.

Hume showed some PUL communal images. This included the Titanic and Olympic, as part of the shipbuilding history of Belfast; the signing of the Ulster Covenant (“a statement of cultural identity and a form of proto-nationalism… signed by 471,717 people, it’s a really strong, community-bonding document”); the Battle of the Somme (“a loyalty to king and country”); and the gun-running of 1914 (harking back to the Scottish borders spirit of non-deference to authority/defending your own).

Hume asked a rhetorical question, “Is there anything really to be proud about?”, as he felt there was.

He began with the poet John Hewitt and his poem Once Alien Here, which begins: “Once alien here my fathers build their house, claimed, drained, and gave the land the shapes of use…” Hume related this to those who came to Ulster in the 17th century, as aliens who worked at the land, shaped it, brought in new farming techniques, and created a farming landscape: “There’s a message there, as there’s lots of people — aliens — in different countries who want to try and shape the future there.”

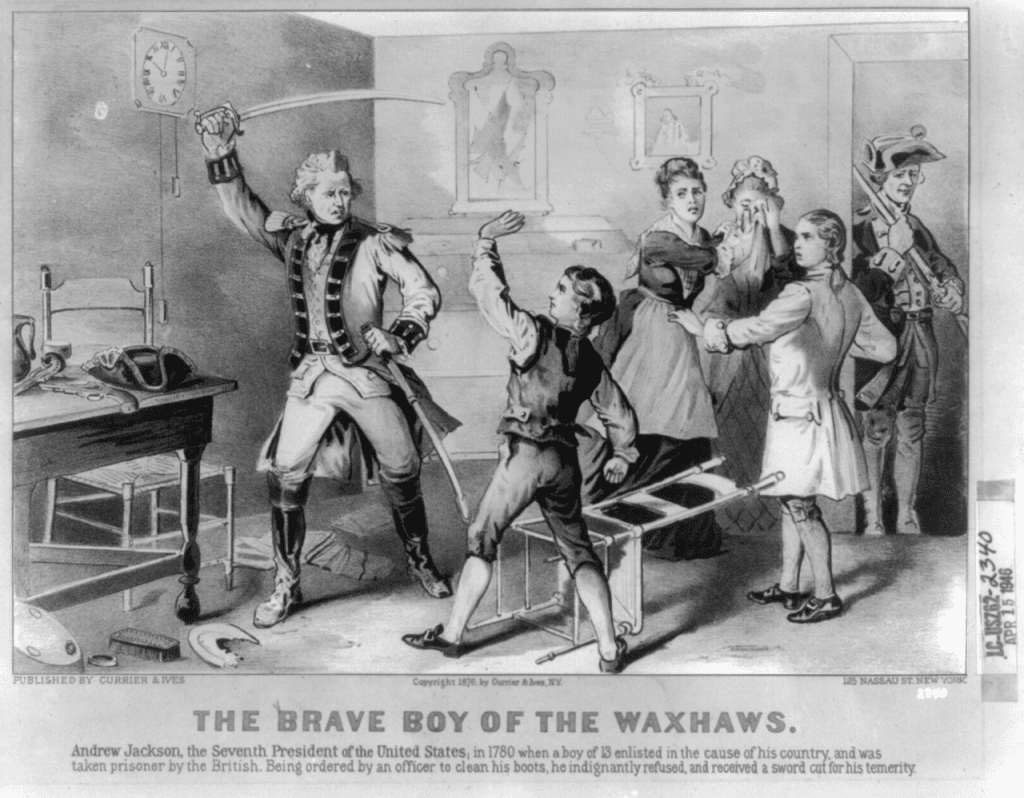

Hume said that we can be proud of the 20 American presidents with Ulster connections, such as Andrew Jackson, known as the “brave boy of Waxhaw” because of his refusal to blacken the boots of a British soldier, resulting in the soldier striking him with a sword, leaving a scar on his face that he carried for life: “If you go to the cemetery of Waxhaw, all of the gravestone surnames are from here.”

Hume cited other notable individuals, such as philosopher Francis Hutcheson (who said it was morally right to challenge the greed of landlords); David Manson (an 18th-century school teacher who used alternatives to chastisement and believed in educating boys and girls together in school); actor Stephen Boyd (Ben Hur film); writer John Steinbeck; writer James McHenry (first to introduce an Ulster family into American literature, in The Wilderness); footballer George Best; William McCrum (who invented the penalty kick); Harry Ferguson (tractor inventor); Frank Pantridge (inventor of defibrillator); Blair Mayne (a founder of the Special Air Service (SAS)); businessman Timothy Eaton (who emigrated to Canada and made his good available by mail order catalogues); explorer and scientist Martha Craig.

Hume also thought about places around the world that connect with the PUL community. His favourite was Orange County, New York: “I don’t think they grow oranges there!” There’s also Belfast, Maine, and Belfast, Ontario, amongst many others: “I collect postcards with Northern Ireland names in the world.”

He summarised: “All of these things are something to be proud of, because we have managed to achieve an awful lot as a community. We’ve been builders, movers, and shapers right through history. And that should never be forgotten.

“People can be quite disparaging about the PUL community; there’s perhaps a class issue in a lot of that… with marching bands and bonfires seen as very working-class by some people within the wider unionist community. It should be kept in mind that these are people who have achieved quite a lot, and everybody has a worth… every community has its worth.

“The PUL community has an incredible history behind it. It has, I think, a big future in front of it, but there are issues that it has. One of those is a bit of education and understanding within itself and the wider community, and that’s something that hopefully can be addressed.

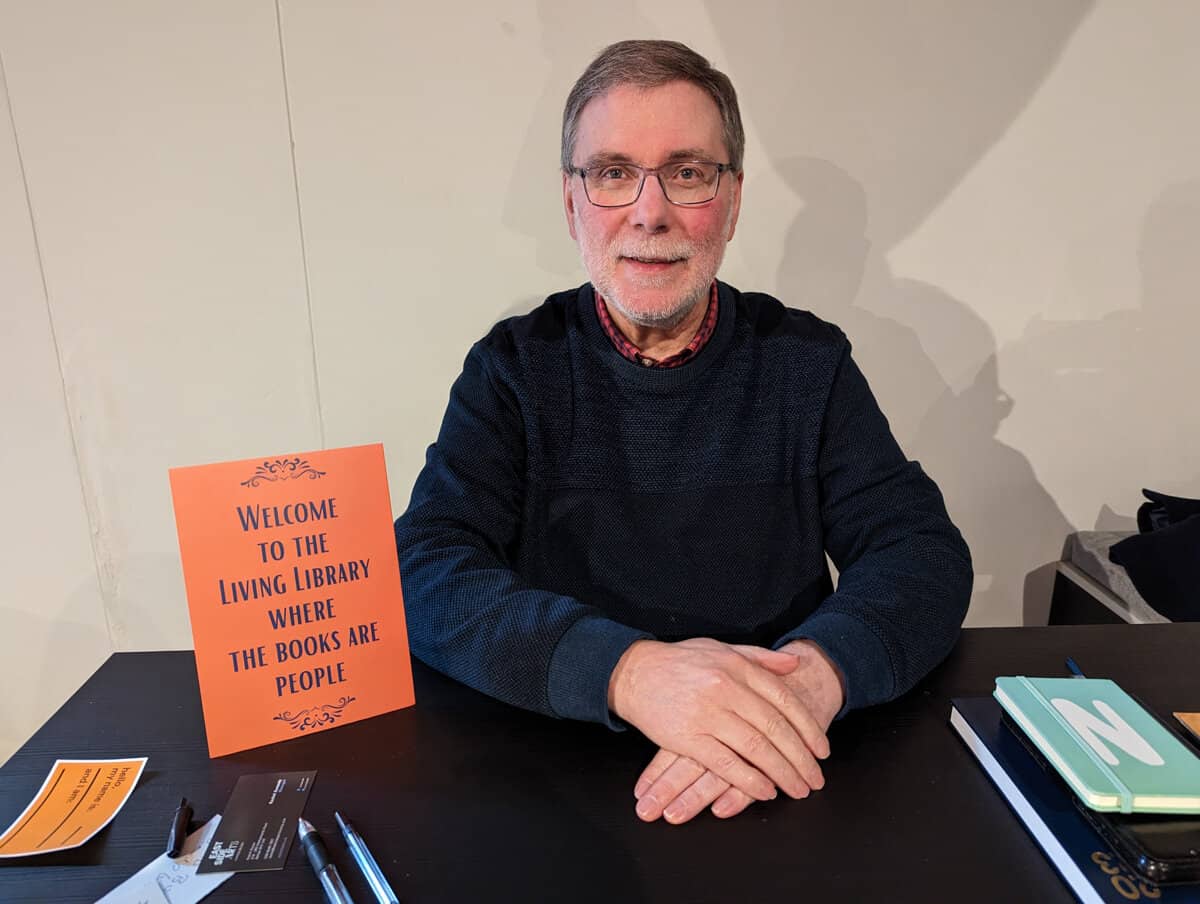

Living library

In the afternoon, visitors could “borrow a story” from individuals seated at tables, ready to share their personal stories. Stories included a loyalist paramilitary’s life before, during, and after the conflict in Northern Ireland; finding pride in one’s local community growing up on the Shore Road; life and times over six decades in a flute band; developing the Irish language in a strong loyalist area of east Belfast; making theatre that gives voice to working-class Protestants; and the development of the Ulster-Scots language.

Archive film exhibition

Throughout the day was a loop screening of clips from Northern Ireland Screen’s Digital Film Archive, including footage of northern and southern Irish at the First World War; Sir Edward Carson addressing a mass rally in Belfast; the Prince of Wales opening Parliament Buildings at Stormont; preparing for the Twelfth on Sandy Row; making a Lambeg drum; Prime Minister Terrance O’Neill at a boys’ club; and Linfield football team victory parade

Partisan Productions: “The Thread”

Brenda Kent spoke about their consultancy’s involvement in bringing together a group of organisations from the PUL community, and learned that they wanted to celebrate PUL culture, educate others, and get themselves seen and heard in a different way.

This led to an approach to Fintan Brady, a videographer with Partisan Productions, who engaged with participants. Brady explained how the conversations much referenced bands, so he went to a band shop on the Shankill Road, which led him to visit another shop next door where the band uniforms are made, spending much time watching the physical stitching.

Brady said that when he spoke with participants, he explained to them that he wasn’t particularly interested in bands, per se, or the politics of it all. Rather, he wanted to know from each person: (1) what does it feel like to you, individually, when you have those colours (uniform) on you; and (2) how does that make you relate to other people.

The result was a six-minute video, “The Thread”, which Brady described as a first draft, “a work in progress”, and he wanted to learn from us viewers and others where to go next with this material and/or other areas of unionist experience, “in a way that will allow us to be confident in what we’re saying”.

He screened the video, which included close-up imagery of sewing machines, the assemblage of band uniforms, and a variety of interviews with band members, including those from the Robert Graham Memorial Flute Band in Crawfordsburn.

In the post-screening discussion, one audience member remarked how she liked the motif of a thread and experiences weaving through generations of a family. Brady responded positively, explaining that what matters is to not be defensive; rather, be confident enough of your own life experiences, memories, and what you’ve absorbed about the world: “That’s your culture. That’s what culture is. It’s not just a set of objects or a set of activities. It’s an understanding of the world… It is formative and always changing; otherwise, it isn’t culture, it’s a historical piece.”

Brady explained how this film focused on bands, “because we had to start the conversation somewhere”, but reached out to the audience for other subject ideas that may fly under the radar, “the other things that folks take pride in”.

His objective is to look at such things differently, so as to give participants confidence that they could obtain cultural support for such “amazing and important” community activities: “In terms of cultural provision, there needs to be diversity; otherwise, it’s not as interesting. It needs to be dynamic. We need to be thinking differently and asking different questions.”

For Brady, he sees a part of unionist culture as finding a progressive way of thinking of tradition, to see such elements in a contemporary light and to make them necessary, “otherwise they could become fossilised”.

He responded to a criticism of negative portrayals of some unionist culture by the media: “A lot [of unionist culture] is extremely positive, and there’s other things that aren’t necessarily positive. So, the question for us is if we’re talking about unionist culture, do we also talk about the things that aren’t positive? That’s fair, isn’t it? It’s about telling the truth and telling it in a way that surprises people.”

Article cross-published at Mr Ulster.

Peacebuilding a shared Northern Irish society ✌️ Editor 🔍 Writer ✏️ Photographer 📸 https://mrulster.com

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.