By Dr Aisling Reid, Lecturer in the School of Arts, English and Languages, QUB

People are not going to care about animal conservation unless they think that animals are worthwhile

David Attenborough

Animals feature prominently in medieval culture (c. 700-1600 CE); stories like Geoffrey Chaucer’s (c. 1340-1400) The Canterbury Tales feature talking roosters and sneaky foxes, while the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1450-1516) are filled with creepy owls and tall giraffes.

Main photo: Hieronymus Bosch, detail from The Garden of Earthly Delights, c. 1480-1505, Prado, Madrid.

Such works afford a fascinating insight into how medieval people thought about animals and provide an opportunity for us to reflect on our own relationship with the curious critters of our surroundings. As we face a climate crisis, where many of the world’s animal and plant species are threatened with extinction, it is now more important than ever that we familiarise ourselves with the history of animal-human relations. It is only by looking into our past that we can fully understand the causes of our current problematic way of relating to the natural world and make the decisive change needed to improve our future.

This two-week exhibition in 2 Royal Avenue (30 October -10 November) samples extracts from one of the most celebrated medieval animal books—The Aberdeen Bestiary, which is an illustrated twelfth-century manuscript held in the University of Aberdeen Library. The book combines descriptions of various animals, both real and mythical, with moral and religious lessons that invite the reader to marvel at the complexity of each individual creature. The aim of the stories and illuminations was not to impart factual information or visual accuracy but rather to convey the wonder, variety, or hidden meaning found in the natural world. Initially, the bestiary was designed for religious instruction within the church; however, it eventually became a sought-after item among affluent members of society for both spiritual contemplation and leisure. Later, the bestiary was translated from its original Latin into various languages, with French being a notable example, thereby broadening its appeal even further.

The book is part of a wider genre of medieval literature known as bestiaries, or ‘books of beasts’. These texts were popular throughout Europe in the later middle ages and were essentially animal encyclopaedias; they were the cultural ancestors of zoos, David Attenborough’s Planet documentaries, Care Bears and The Lion King.

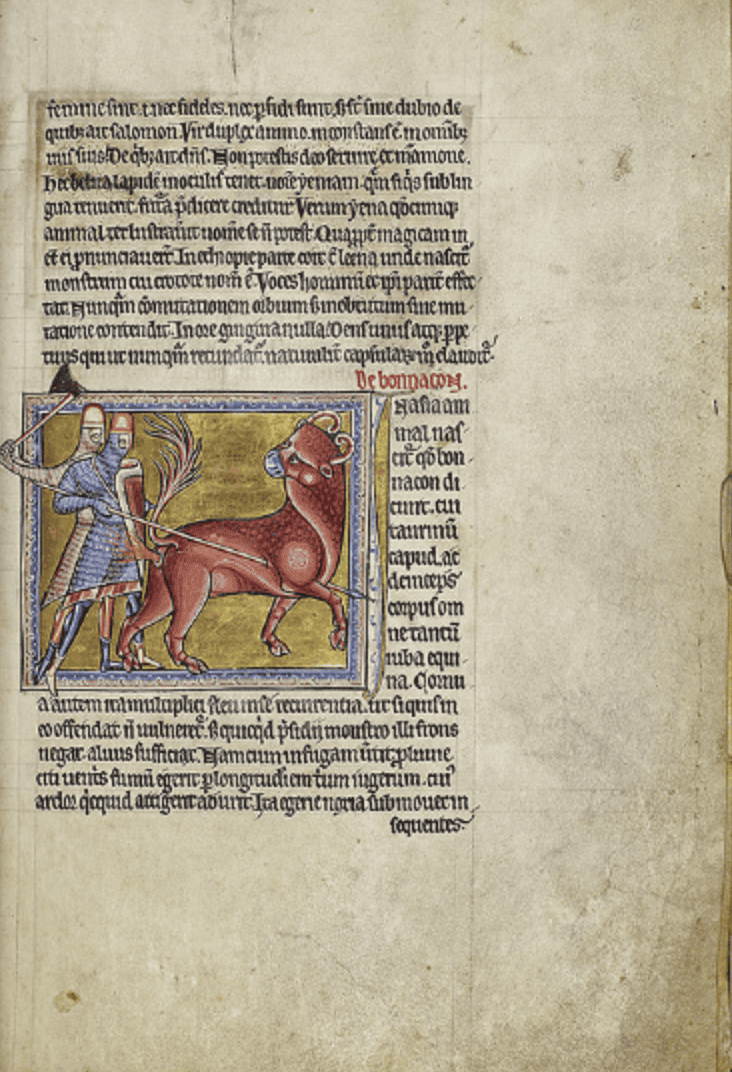

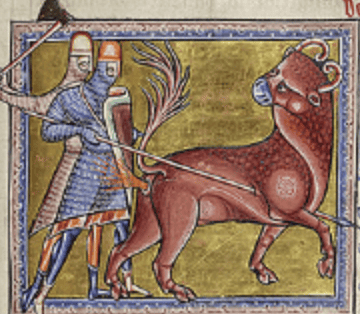

Each entry would typically contain an illustration of a particular animal, followed by a brief description of its appearance, its characteristics and finally, some religious information on the moral lesson it provides. Animals were therefore considered to be important creatures with distinct personalities who were there to benefit humanity and improve society. The Aberdeen Bestiary includes fantastic beasts, like unicorns, a basilisk and a phoenix. Other animals are less majestic; the ‘bonnacon’, for example, is described as a composite animal made from the head and body of a bull, the neck of a horse and horns that curl backwards. When threatened, it defends itself by excreting flaming hot faeces a distance of three acres! (Yes, you read that correctly):

In Asia an animal is found which men call bonnacon. It has the head of a bull, and thereafter its whole body is of the size of a bull’s with the maned neck of a horse. Its horns are convoluted, curling back on themselves in such a way that if anyone comes up against it, he is not harmed. But the protection which its forehead denies this monster is furnished by its bowels. For when it turns to flee, it discharges fumes from the excrement of its belly over a distance of three acres, the heat of which sets fire to anything it touches. In this way, it drives off its pursuers with its harmful excrement (fol. 12r).

The Bonnacon, The Aberdeen Bestiary, fol. 12 r

Despite its unusual character, the legend of the bonnacon, this mythical creature wielding excrement as a unique defence mechanism, nevertheless imparts important lessons about our relationship with the animal kingdom and our wider environment. The book’s description of strange animals reminds the readership of their ability to surprise and shock through their super-human abilities; while the bonnacon’s excremental abilities might initially seem unbelievable, its technique is, in fact, common in the animal kingdom, as is seen for example, when skunks emit foul odours to escape their predator. The bonnacon therefore reminds us of the unconventional aspects and marvellous abilities of wildlife— quite literally deflating humanity’s sense of its own superiority!

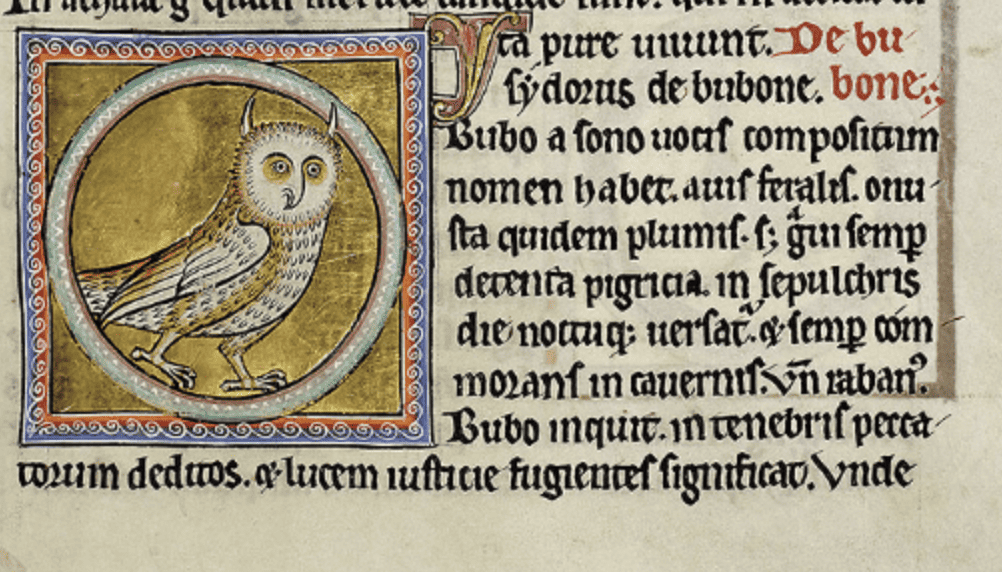

Another fascinating creature represented in the Aberdeen Bestiary is the owl; which is described as a lazy animal which sleeps all day, living in caves and graveyards. The author writes that the owl ‘signifies those who have given themselves up to the darkness of sin and those who flee from the light of righteousness.’ (fol. 50r):

The owl gets its name from the sound it makes, because its mouth speaks when its heart is overfull, for what it thinks about in its mind, it utters with its voice. It is said to be a filthy bird, because it fouls its nest with its droppings, as the sinner dishonours those with whom he lives, by the example of his evil ways. It is weighed down with its plumage, as the sinner is with an excess of carnal pleasure and with fickleness of mind; but it is truly hampered by the weight of its sloth. It is hindered by the weight of its idleness and sloth, as sinners are lazy and slothful in acting virtuously. It spends its days and nights around burial places, as the sinner delights in sin, which is like the stench of decaying human flesh. For it lives in caves like the sinner who will not emerge from darkness by means of confession but detests the light of truth. When other birds see the owl, they signal its presence with loud cries and harass it with fierce assaults. In the same way, if a sinner comes into the light of understanding, he becomes an object of derision to the virtuous. And when he is caught openly in the act of sinning, his ears are filled with their reproaches. As the birds pull out the owl’s feathers and tear at it with their beaks, the virtuous censure the carnal acts of the sinner and condemn his excesses. The owl is known, therefore, as a miserable bird, just as the sinner, who behaves in the way we have described above, is a miserable man (fol. 50v).

The Owl, The Aberdeen Bestiary, fol. 50r.

Those who wish to live a useful life are advised to think of the bad example set by the owl and act differently. By drawing parallels between human and animal behaviours, the author problematises the distinction between the two. The text suggests that humans and animals are, in some respects, similar, or co-involved. In this regard, the text demonstrates an interest in thinking through the nature of animality and by extension, humanity; that is to say, what is the proper place and role of humans and animals in the world? What is the nature of our co-existence and how do we share our surroundings?

The non-anthropocentric outlook that the book demonstrates anticipates the thinking of the animal theorist Melanie Challenger, whose 2021 book How to be an Animal is a timely reminder of our own ‘animality’. Challenger argues that humans mistakenly regard themselves as ‘exceptional’ creatures, when in fact they are simply one type of being among the many millions in the world:

All that humans have tended to agree on is that we are somehow exceptional. Humans have lived for centuries as if we’re not animals. There’s something extra about us that has a unique value, whether it’s rationality or consciousness. For religious societies, humans aren’t animals but creatures with a soul. Supporters of secular creeds like humanism make much of their liberation from superstition. Yet the majority rely on species membership as if it is a magical boundary. This move has always been beset by problems. But, as time has passed, it has become harder to justify. Most of us act according to intuitions or principles that human needs outrank those of any other living thing. But when we try to isolate something in the human animals and turn it into a person or a moral agent or a soul, we create difficulties for ourselves. We can end up with the mistaken belief that there is something non-biological about us that is ultimately good or important. And that has taken us to a point where some of use seek to live forever or enhance our minds or become machines

Melanie Challenger. How to Be Animal: A New History of What it Means to Be Human (London: Canongate Books, 2021).

Melanie Challenger

Looking at animals in the literature and art of the past therefore presents us with an opportunity to reflect on how and why our attitudes to the world has changed, in tandem with how we understand ourselves. Indeed the cultural critic John Berger considers our relationship with animals to be fundamental to our relationship with one another. In his 1977 essay ‘Why look at Animals?” he perceptively recognised that our conceptualisation and treatment of animals often prefigures how we relate to other people. Objectification of animals as a resource that serves our needs inevitably anticipates a cold economic objectification of one another, wherein people are esteemed not as means in themselves but as a means to an end:

This reduction of the animal, which has a theoretical as well as economic history, is part of the same process as that by which men have been reduced to isolated productive and consuming units. Indeed, during this period, an approach to animals often prefigured an approach to man. The mechanical view of the animals’ work capacity was later applied to that of workers. F.W. Taylor who developed the ‘Taylorism’ of time-motion studies and ’scientific’ management of industry proposed that work must be ‘so stupid’ and so phlegmatic that he (the worker) ‘more nearly resembles in his mental make-up the ox than any other qype’ Nearly all modern techniques of social conditioning were first established with animals experiments

John Berger. Why Look at Animals? (London: Penguin, 2009), 13.

John Berger

The integration of animals as symbolic representations of human behaviour in medieval literature and art challenges the traditional boundaries between humans and the animal world. These cultural artefacts provide a unique window into the medieval perspective, offering us a deeper understanding of how people of that time perceived themselves, others, and their environment.

Perhaps more importantly for the ecocritical challenges we face today, the idiosyncratic depictions of medieval animals imagine the world not from an anthropocentric perspective but quite often from the point of view of the animal. In this regard, the tales encourage us to reflect on the shift that has occurred over the course of the past 1000 years, from a respectful relationship with the environment and its creatures, towards the current era of the Anthropocene, where the world and its furry occupants are often viewed primarily as a resource to fulfil human needs.

‘Curious Creatures: Human-animal relations in Medieval culture’ runs from 30 October to 10 November in 2 Royal Avenue, Belfast. The venue is open 10am-6pm, Monday to Sunday. All are welcome to attend.

QPol is the ‘front door’ for public policy engagement at Queen’s University Belfast, supporting academics and policymakers in sharing evidence-based research and ideas on the major social, cultural and economic challenges facing society regionally, nationally and beyond. Website: qpol.qub.ac.uk Email: [email protected]

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.