Shortly after my wife and I moved into our house, I was sitting on our new front step when a woman stopped her car on the street outside.

“Hello?” she said.

“Hello,” I said.

“Can I help you,” she said.

I looked about, a bit unsure how to help this woman help me. “No thanks, all good,” I said.

“Do you live here?”

“Yes. We just moved in. About a month ago.”

“Oh. Are you renting?”

“No, we bought the house.”

“Oh. Okay. I just wanted to check.”

“Okay. Do you also live -”

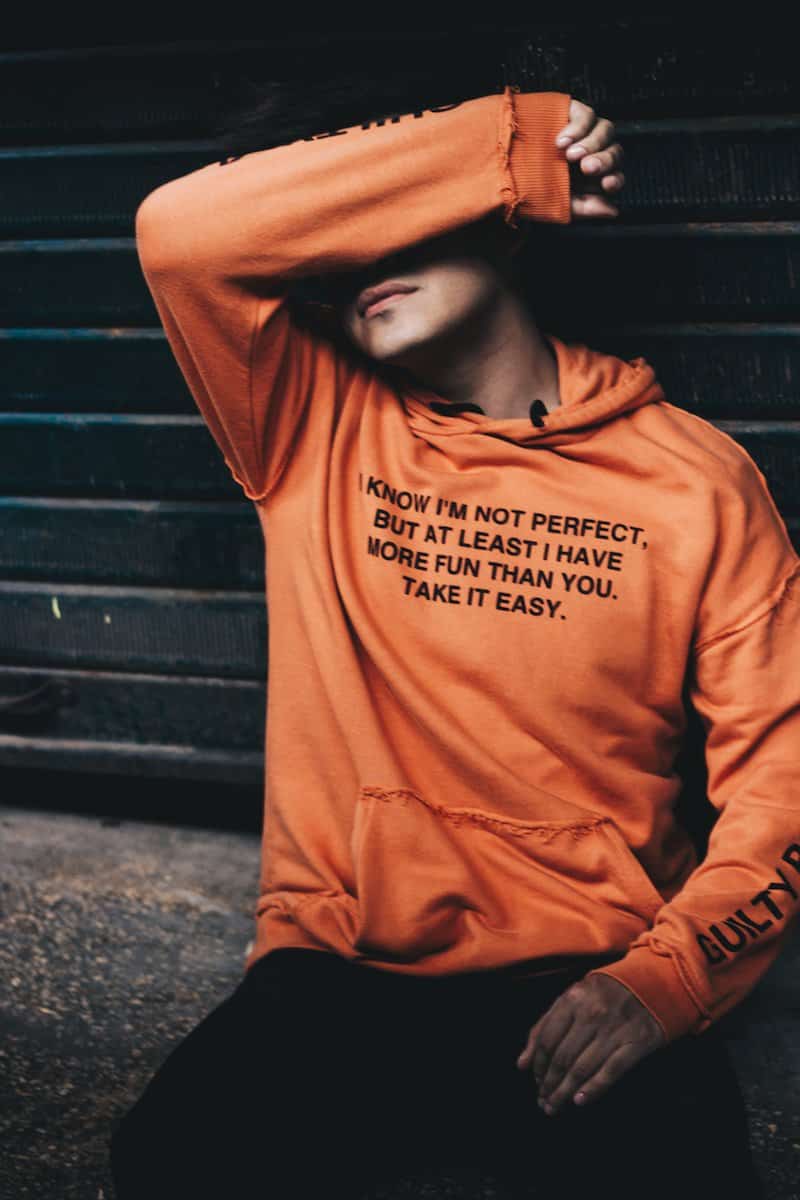

“It’s just, you look so young. And you’re wearing a hoodie.”

“Oh.” I did smile at this point. “Yeah,” I said. “Just having a casual one today.”

“Yes, you see we’ve been warned to look out for young people in hoodies, and I just wanted to check, you know, that you weren’t robbing the place or anything.”

“Oh.”

“Yes, well, all the best.”

She drove on.

Reader, I’d like you to know that I’m wearing a hoodie as I type this. I work from home these days. Comfort is key. I often feel a little self-conscious walking about the neighbourhood, though the same woman smiles at me these days, regardless of what I’m wearing. She asks my daughter how school is. I’d hazard a guess though that if I decided to teach my daughter tennis out on the street where she pulled her car in that time, she’d take against it.

On the street I grew up on, summer meant hanging up the hoodies, getting into shorts and short sleeves, and getting out onto the road, tennis rackets in hand. The road markings left a perfect miniature court shape on which my friends and I played full Grand Slam tournaments. The umpire would watch for serves which were marginally wide of the black line of tar down the middle of the road, and also for cars.

You don’t need to know much about tennis to name the Big Three. This year is the twentieth anniversary of Roger Federer’s first Wimbledon title. Not only would his 2003 win be the first of a record-equalling streak of five, but it would also usher in an unprecedented concentration of success in men’s singles, lasting two decades and on into the present day. Seventy-nine grand slams have been contested over those twenty years, sixty-five of which have been won by one of Federer (20), Rafael Nadal (22), or Novak Djokovic, who surpassed Nadal last month when he claimed grand slam number 23 at the French Open.

My street tennis era was the one preceding that of the Big Three. My friend Shane was Pete Sampras. Lenny was Andre Agassi. Steph was Steffi Graf, despite being four foot tall on her tiptoes. They were all good. They played outside Lenny’s house. Centre Court. I was one of a rotating cast of extras on the lower courts, further down the street where it was bumpier and the lines weren’t as clear. I had stints as Boris Becker, Michael Stich, Goran Ivanisavic and Thomas Muster, occasionally getting the call to make up the numbers for doubles on Centre Court.

We ran our tournaments in a fashion more akin to the high-strung drama of World Wrestling than the gentile decorum of the All-England Club. No strawberries. We were too young to have seen John McEnroe, but perhaps channelled a generational craving for greater controversy. Doubles games almost always ended in a default win, with one pair going into a full-on screaming match, bellowing at one another in terrible American accents. New characters inserted themselves into the narrative each year. A girl called Trish moved in, two years our senior and initially dripping with condescension as she watched us kids play our kid tennis. But before long, she was immersed completely in rotating roles as Martina Hingis, Lindsay Davenport and Jennifer Capriatti. I developed an affection for an affable Aussie named Pat Rafter and, in 2001, found myself wildly conflicted when real-life Rafter faced my former alias Goran Ivanisavic in the actual Wimbledon final.

The Big Three came along as we were finally ageing out of our shtick. On our television screens, the tennis went up a gear. But the next generation of kids on the street didn’t have the same raw material for drama. Domination just isn’t all that fun.

Though it still is remarkable. A period like this arises, not just through a gulf in standards in a given year, but remarkable longevity on the part of all three. Djokovic had just turned 36 when he won this year at Roland Garros, the same age Federer was for his last title. In those two finals, both men defeated opponents in their mid-twenties, historically the years when tennis players have peaked.

Elite athlete longevity isn’t confined to tennis. Be it football’s Lionel Messi, or Marta who is about to play in her sixth World Cup for Brazil, snooker’s Ronnie O’Sullivan, rugby’s Johnny Sexton or American Football’s Tom Brady, almost every sport has recently witnessed players bucking the historical trend of precipitous decline past age thirty. Social scientists and epidemiologists share an interest in Age-Period-Cohort analysis, through which different effects of time can be disentangled. Age is the easiest of these to understand, particularly when we think of a physical attribute like speed. A randomly selected group of 23-year-olds and 63-year-olds are lined up and told to run a hundred metres. Unless our random sample has included Linford Christie (born 1960), we’re expecting most of the 23-year-olds to outpace the 63-year-olds. Ageing has known effects on speed.

It is also true that, historically, athletes at all levels have gotten faster. The pace achieved by Roger Bannister for his unprecedented four-minute mile of 1954 would fail to qualify him to run the 1500 metres at next year’s 2024 Paris Olympics. Since 1960, the world record at that distance fell by 10 seconds for men, and 30 seconds for women. Across history, elite athletes have gotten faster.

Cohort effects are a particular interplay between the first two. Does being a certain age at a certain period influence how your life unfolds? The classic example is having been a child during a disease outbreak or environmental disaster to which children are particularly vulnerable. So, while life expectancy has also increased historically, if we graph out life expectancy for each successive year’s birth cohort, we see a graph that isn’t entirely smooth: someone born in 1910 was more vulnerable to having their life shortened by Spanish Flu or its after-effects than someone born in 1900 or in 1920.

Possible cohort effect explanations for athlete longevity include theories around parenting norms and pre-digital childhoods. Novak Djokovic is just over a year younger than I am. Granted, he was spending his youthful summers playing at a higher level than Centre Court by Lenny’s house, but still, those summers were outdoors. Because what else was there in the early 90s? Computer games were rubbish and the internet was unheard of. Go play a real game or watch two flies go up a wall. Either way, get out my sight, scram.

In this part of the world, we were about to experience, in a new and visceral way, the high-profile disappearances and/or murder of several young children. The names of Jamie Bulger, Madeleine McCann, Robert Holohan, Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman would all become household bywords for danger. This did not correlate with underlying rise in crime rates, rather with the emergence of twenty-four-hour news. Has the chill wind of their stories caused a generation of parents to be over-cautious? Is that why street tennis might look like an oddity in vast swathes of urban residential spaces? It could even be a double-impact. Fewer kids allowed out and play, and more children ferried by car to structured activities, rather than being left to walk or cycle, thus more traffic and the sense of streets becoming more dangerous.

Cohort effects fascinate me, especially thinking through the outworkings of the major events in my lifetime: 9/11; the 2008 financial crash; and COVID-19. During lockdown, I wrote about a new social and spatial geometry people were learning to observe, reshaping how they interacted with friends and family, tensely holding the shared responsibility for public health and safety tightly within their very bodies. Most of what I see day to day in South Belfast suggests that most of us have exhaled and let that go. And yet, I still see people in the habit of walking round a car into the road when another pedestrian is coming against them, rather than pass too closely. Can my six-year-old daughter remember any other way to walk on a footpath?

The Republic of Ireland’s women footballers are about to contest their first World Cup. Their opening game is against co-hosts Australia, in a sold out 80,000-seater stadium. An estimated 30,000 tickets were bought by Irish fans, the majority now living there permanently. Many of those who emigrated after the Irish economy tanked in 2008 never moved home. For a generation of Irish, it is normal to only see some of one’s closest school friends a few times per decade in adulthood. The long-run effects on those emigrants, on those who stayed at home or came back, and the places they left and went to, will unfold before us over many years.

On its face, it seems hard to deny that some sort of cohort effect has impacted elite sport, with athletes born between the mid-1980s and early 1990s having achieved more and for longer than any previous generation. Remarkably, the elite individual award in men’s football, the Ballon D’Or, has been awarded to a player in his thirties each year since 2016, having been awarded to players in their twenties in each year from 2004-2015 (Lionel Messi and Christiano Ronaldo each received the award either side of thirty). Is this because they grew up permissive parents and glitchy Sega Mega Drives? Alternative explanations abound. Advances in Sports Science. Improved nutrition and athlete care. Access to TV analysis and coaching during childhood.

Then there’s money. Lots and lots of money. As well as hyperinflation in player wages, these older millennials were just the right age at the right moment to be among the first global social media stars. Does that make them better athletes? Probably not, but if you have millions of devoted followers compiling your best work onto video montages, that can’t do any harm to your perceived value, to elite teams, or indeed to those who vote for individual awards.

It should be said in addition that the emergence of a relatively small number of superstars doesn’t necessarily speak to the abilities of an entire cohort. Returning to tennis, why weren’t any of the other players born between 1983 and 1987 able to share in the dominance? Two Andys, Murray and Roddick, each took turns trying to make a Big Four of it, but ended up with just four Grand Slams between them. And if you watch any of Messi’s highlight reels, you’ll see him put the ball through the legs of many a player the exact same age as he.

I’ve taken off my hoodie. I went for a walk, but it was too warm for long sleeves. I passed another neighbour with his dog. He’s about my Dad’s age. He wears the same three woolly v-neck jumpers on rotation. Not unlike the ones my Dad wears. He probably thinks the same when he sees me. Same three hoodies that lad has. And you know what? We’re creatures of habit. I’ll probably never make the switch to woolly v-necks at this stage. When I’m his age, there’ll be hoodie shops for the likes of me and my generation. The young people will shake their heads. When did those ever look good? I might tell them about the time Pharrel Williams caused a stir by wearing one to Centre Court, the real one at Wimbledon. Then again, I might not.

John Moriarty is a writer of fiction and non-fiction. He has lived in Belfast with his family since 2009 and holds a PhD in Sociology from Queen’s University. You can find links to his short stories on johnmoriarty.net, or find him on Twitter or Mastadon.”

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.