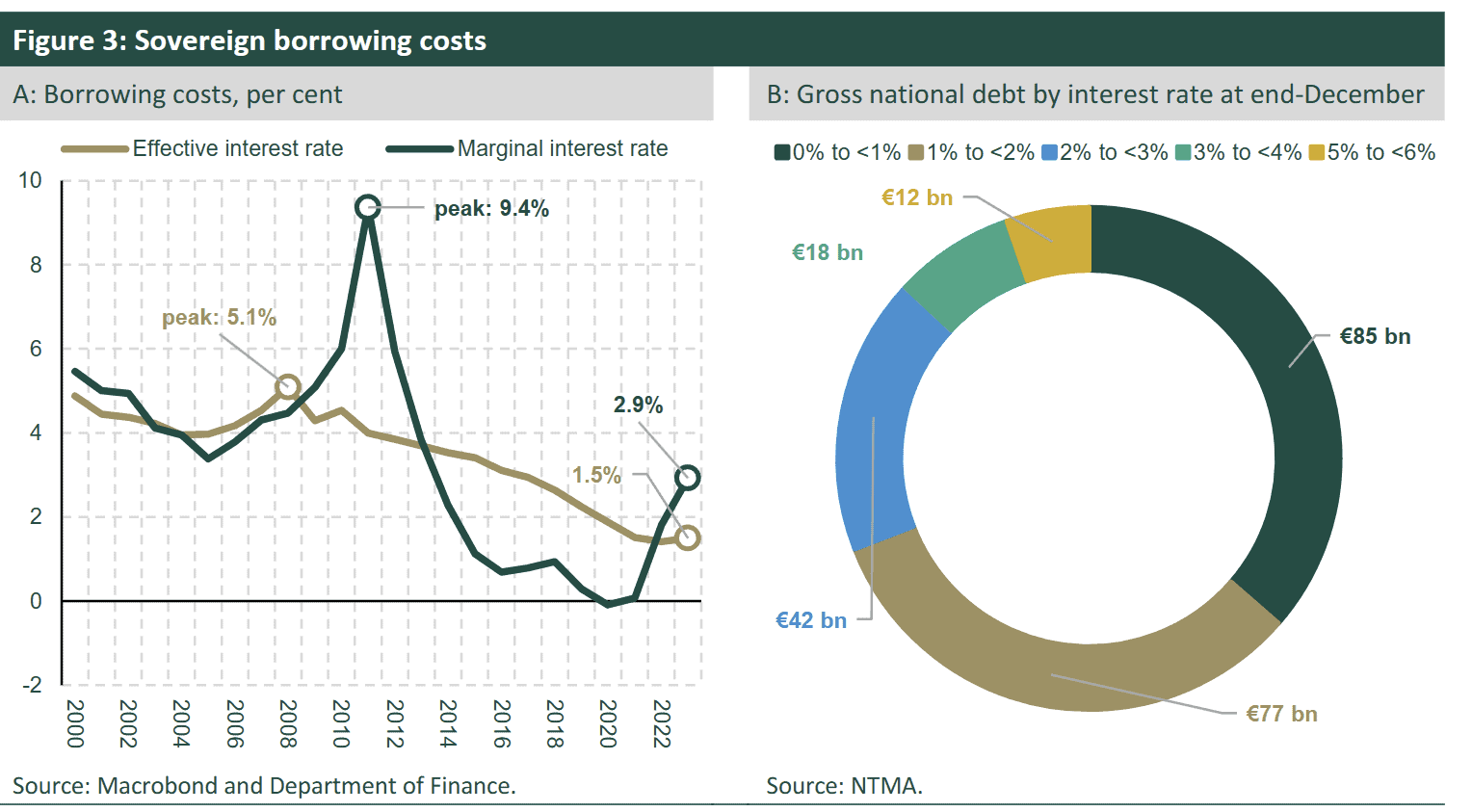

It is generally recognised that the IDA has been one of the most successful state agencies charged with attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) in the world. Less attention has been paid to the outstanding role played by the NTMA in managing Ireland’s national debt. The agency avoided any threat of a sovereign debt default in the 2009-2012 financial crisis and banking crash, thus giving Ireland a very high debt rating and low risk profile as far as creditors were concerned, reducing the interest rate Ireland can borrow at ever since.

The agency then took advantage of near zero interest rates during the Pandemic to build up a €30 billion cash pile, pay off older more expensive debts, improve the national debt maturity profile by avoiding future “cliff edges” in debt repayments becoming due, and locking in those low interest rates by borrowing at fixed rates. This increased borrowing helped the government ensure the economy kept afloat during the pandemic and could recover quickly afterwards with relatively few businesses going to the wall during that crisis.

When a country borrows heavily at low interest rates during a time of rising inflation, it is effectively saving money. If you borrow €100 billion at 0% interest and pay it back 10 years later when there has been (say) 30% inflation in the meantime, you are effectively paying back 30% less in real terms. The €100 billion you pay back 10 years later could only have bought you €70 billion worth of goods at the higher inflated price prevalent then. Such was the eagerness of investors to put their money in a “safe haven” such as Ireland during the crisis, they were prepared to countenance such potential losses in order to avoid the risk of even greater losses elsewhere.

Of course interest rates have now caught up with inflation, resulting in borrowers having to pay back more capital and interest, in real terms, than they had borrowed. But by this stage the NTMA has already refinanced much of its outstanding, ongoing , and forthcoming debt repayment costs by borrowing at 0% and locking in that interest rate by borrowing at fixed rates.

In reality countries borrow all the time, even if only to pay back previous debts and and pay off interest bills. In Keynesian economics, the idea is to borrow more at times of recession to keep the economy afloat and then pay back those debts and reduce borrowing when the economy is buoyant. In theory that should “smooth out” the boom and bust cycles economies are prone to experience due to external shocks or internal instability.

It also prevents many businesses going to the wall and causing other, profitable, businesses to fail because their invoices haven’t been paid as a result. Any rise in economic disruption, unemployment, or social distress which would otherwise occur is reduced, and with it the costs to the state in terms of social welfare, redundancy, business support and healthcare bills. It also helps to keep the government tax take rising if the economy isn’t crashing or flatlining. Unemployed workers don’t add to economic productivity or contribute to state coffers. It pays to keep them at work.

That is the theory, and it worked very well during the pandemic, especially for countries like Ireland which were able to borrow heavily due to the very rapid recovery in our public finances after the financial crash and the reduced interest rates we could then borrow at.

In practice, governments, find it very difficult to turn off the cash spigot when the economy improves, especially coming up to elections. Consumers have gotten used to energy credits, government expenditure increases and tax hand-outs at budget time, and expect more of the same even when the cost of living crisis has abated somewhat. Of course low paid workers may continue to need support, but the electoral calculus demands that the benefits be spread as widely as possible, including to people who may no longer need them.

That is the issue facing the Irish government today with a general election due within the next year. Thanks to the continued buoyancy of income, consumer and corporate tax receipts, the state finances are in huge surplus, and yet the economy is in danger of overheating if further large stimulus is applied.

What happens then is that demand exceeds supply, resulting in a rise in inflation wiping away much of the benefits for ordinary people, and reducing Ireland’s competitiveness abroad and attractiveness for further investment. We are in danger of entering a boom and bust cycle again.

In fairness, the government has recognised the danger, and is salting away €6 billion p.a. in various investment vehicles for use only in the event of an economic crisis and to fund the increased costs of an aging population and climate change mitigation in the years ahead. Note there is no provision for funding a United Ireland, even on a contingency basis, for all the talk of a “shared island.” The focus is on addressing the “four D’s” of demographics, decarbonisation, digitalisation and de-globalisation.

Despite some economic headwinds, the government is projecting an €8.6 billion surplus this year (up from a €8.3 billion surplus last year) and a projected €38 billion surplus over the next four years. However these figures are very tentative and subject to potentially large fluctuations in corporate tax takes in particular. Some of the increase in corporate tax takes are seen as “windfall” and unlikely to last indefinitely, and without them the government finances would be in deficit. So extreme caution is required in assessing such projections.

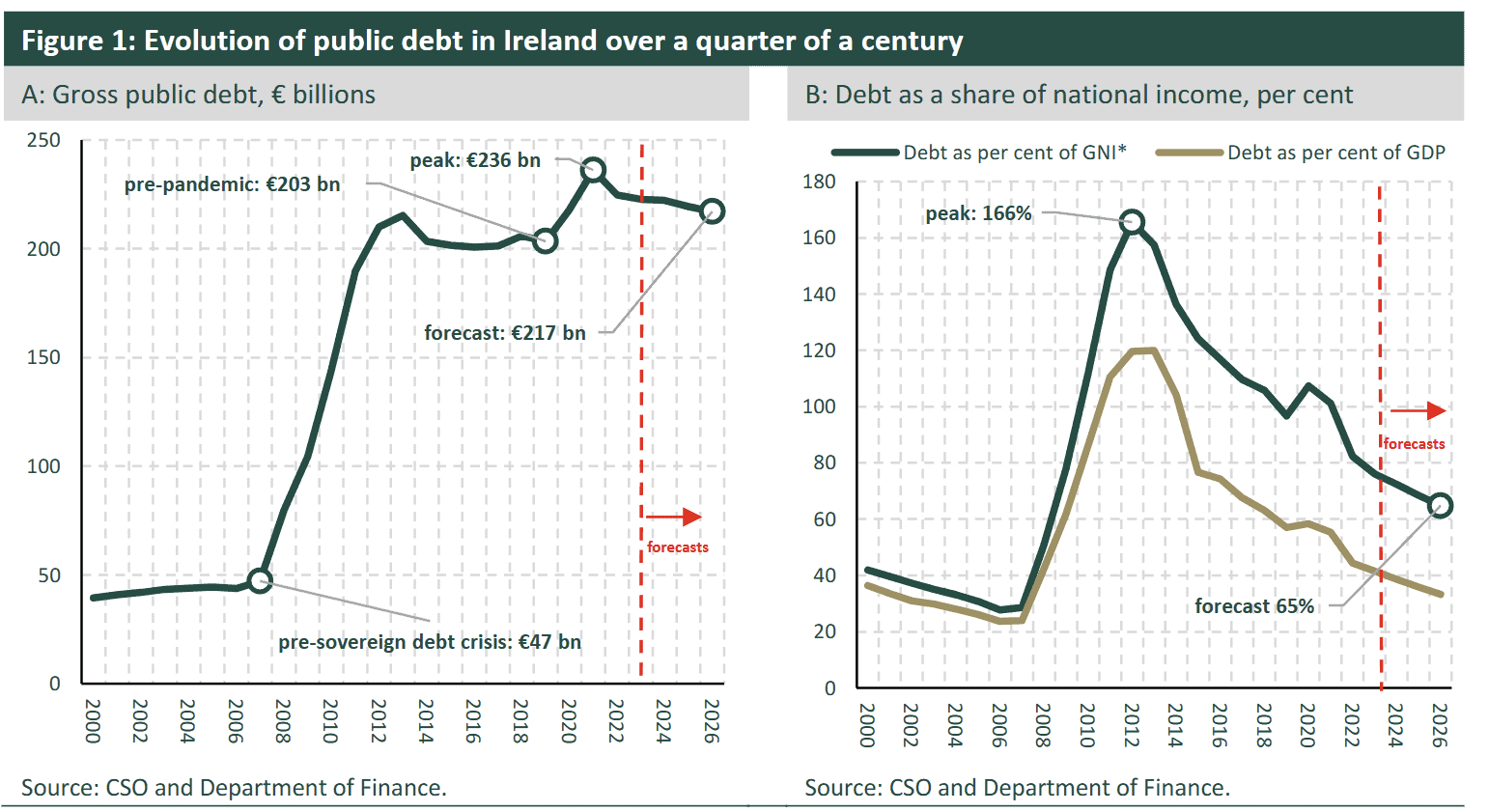

Previous performance is never an absolutely reliable guide to future outcomes, but it is worth recording just how extraordinary past performance has been:

Chart A) Gross debt shot up during the financial crisis from less than €50 Billion to over €200 billion but has remained roughly constant since, although it rose from €203 billion to €236 during the pandemic. Note that it is projected to decline by €19 billion to €217 billion over the next 3 years – despite the injection of funds into the long term investment vehicles. When cash balances and assets in state investment funds are taken into account, net debt is about €40 billion lower than gross debt.

Chart B) When viewed as a proportion of the size of the economy, however, the decline has been precipitous, both as a proportion of GDP, and as a proportion of GNI*, which is a more realistic estimate of the size of the Irish economy taking into account of the activities of global corporations who report their revenue and profits here, even when much of that production and revenue is generated abroad.

In terms of the internationally recognised measure of debt sustainability, which is debt/GDP, Ireland’s national debt has declined for 120% of GDP in 2012 to about 40% now. Even in terms of the more realistic debt/GNI* measure, it has declined from 166% of GNI* in 2012 to a projected 65% in 2026. That is why international investors are prepared to invest in Irish debt at such low interest rates. For them, their investments are effectively risk free.

Fig 3 Chart A) The interest rate Ireland pays on new debt has declined from a peak of 9.4% in 2011 to 0% in 2021-22 but has risen to 2.9% in line with global interest rate increases generally in more recent times. The average interest rate paid on the total Irish debt has declined from 5.1% to 1.5% and absorbs about 1% of Ireland’s income. 1.5% is still less than our current inflation rate of 2.9% (which is projected to decline to 2.1% by the end of the year). So we are still paying back less than we borrowed in real terms, or in terms of current purchasing power, although that is expected to change in future years.

All of these numbers place Ireland near the top of the EU league table of best performing member states with the exception of national debt/capita which, at €42,000, is high. But then our GDP per capita is also the second highest in the world after Luxemburg, and over twice that of the UK, so our ability to service and pay back those debts is higher than almost every other country.

By way of comparison, the UK, whose dept/GDP ratio has been rising towards 100% , the interest the government pays on national debt has reached a 20-year high with the rate on 30-year bonds rising above 5%. and with 10 year bonds yielding 4.34%, a rise of 1% in the past year. The UK also borrowed largely at variable rates, meaning their interest bill has increased precipitously. As a result the UK national interest bill absorbs 4.4% of its GDP and 9.7% of its total government expenditure. The equivalent figures for Ireland are approximately 1% and 3%.

There is a “snowball” effect in all of this. As the debt/GDP ratio declines so does the average interest rate payable on that debt and the total interest payment burden as a proportion of government expenditure as a whole. That means more money is available to reduce debt further or improve social services or economic productivity meaning than the economy grows more and the tax take rises. Debt interest repayments become increasingly less onerous on the national purse.

So we are in a virtuous circle right now, but we were at where the UK is now as recently as 2012. Let us hope the memory of that episode will encourage the government to take a prudent attitude now, and not let electoral pressures return us to a boom and bust cycle. The government set a ceiling of 5% growth on government expenditure a few years ago, but have broken it every year since. That was not a huge problem when inflation was over 5%, but could become a problem now that inflation is back down to a more sustainable 2-3%.

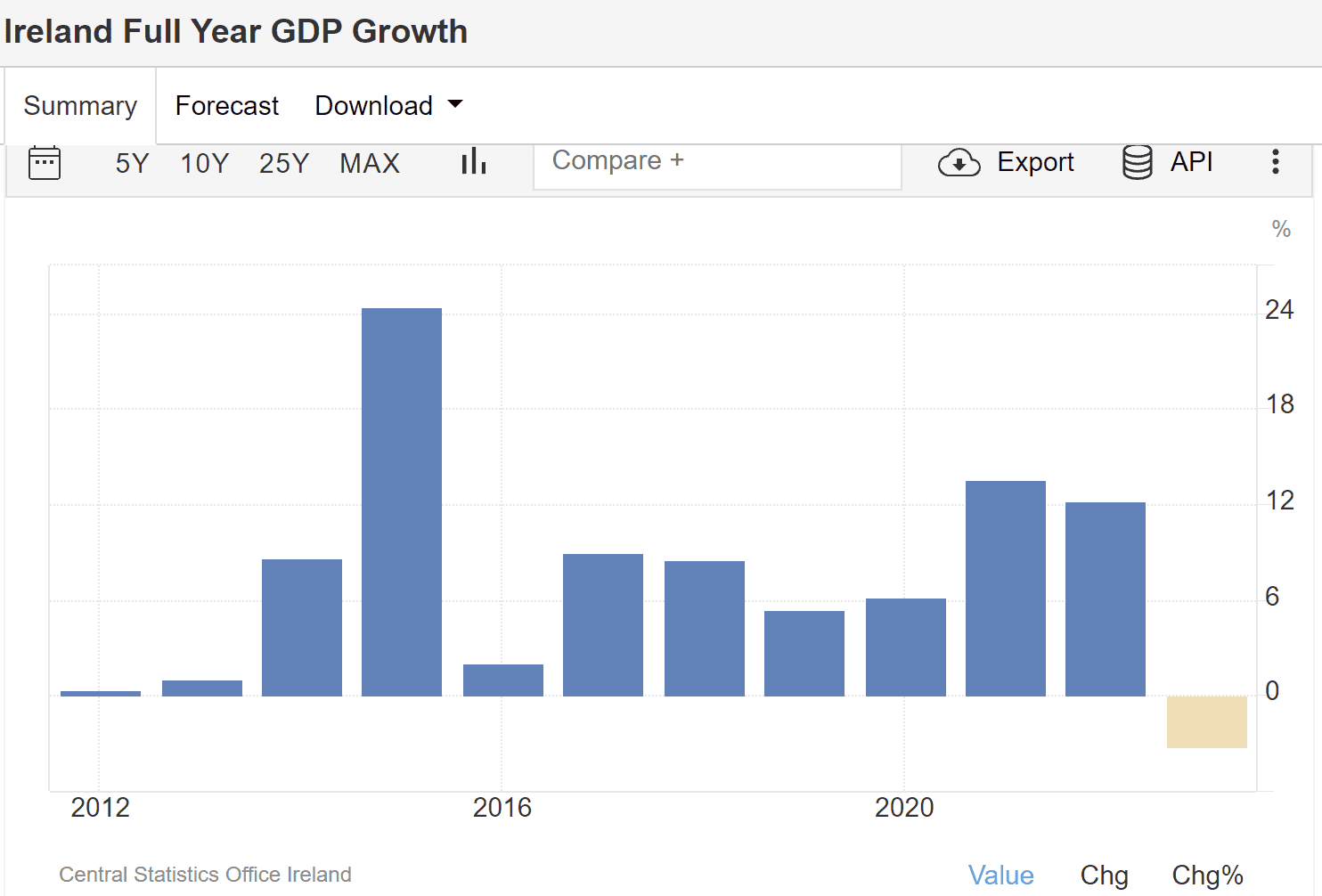

The economy is projected to grow by 2-3% p.a. for the next few years, which is certainly a lot more sustainable that the stratospheric growth rates of the past (some of which were more accounting than real) and should allow some of our infrastructure deficits in public housing, healthcare and transport to be addressed.

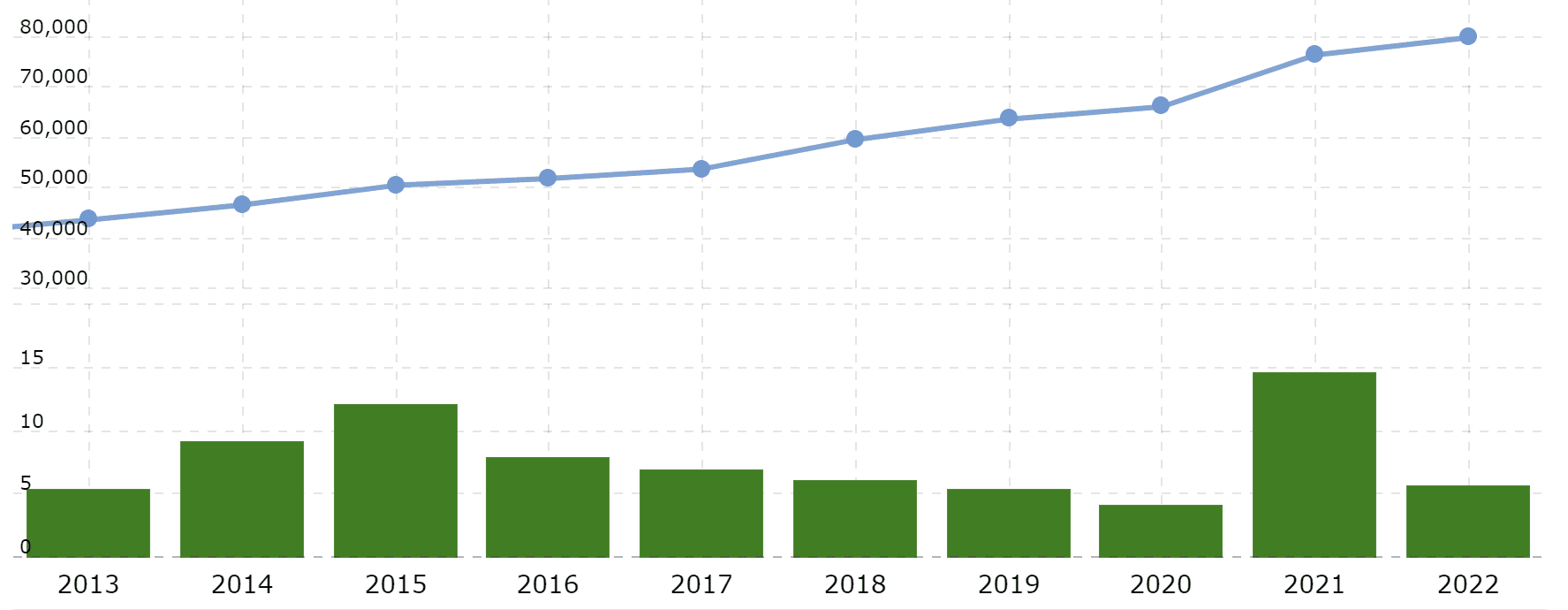

The workforce increased by another 90,000 last year, to 2.7 million, which is almost three times the 1 million jobs in the economy as recently as the 1980’s. 50,000 of those extra jobs went to inward migrants, and all those extra workers need housing and transport solutions, and schools and hospitals for their families. Our total population increased from 5.1 to 5.3 million last year, which means our infrastructure has a lot of catching up to do.

The data actual shows a decline in Irish GDP in 2023, which is due to a huge fall off in pharmaceutical exports once the Pandemic was officially over. However the “real” or domestic economy remains buoyant despite the surge in inflation and interest rates, as witnessed by the continuing rise in employment, consumer expenditure, and VAT and income tax receipts.

Growth in GNI terms has been much less volatile, stripping out huge variations in multinational exports and accounting practices, and more accurately reflects the actual health of the Irish economy. This is a record of outstanding success, but there are also warning signs on the horizon, which brings me to the SWOT analysis chart at the top of this OP.

Our debt profile is outstandingly good, but global interest rates are on the rise nevertheless. Our economy is still growing, but infrastructural bottlenecks put future growth potential at risk. Ireland has lost out on some big global corporate investment decisions recently because our planning and physical infrastructure was not deemed adequate. Far too much of our corporate tax take comes form very few companies, and is vulnerable should those companies relocate, change their accounting policies, or fail.

There is a national strategy to address our infrastructure deficits, but it lacks ambition and is hamstrung by planning approval and building industry capacity bottlenecks. The investment in long term savings vehicles is welcome, but is it a case of too little, too late? The costs of an aging population (Demographics), climate change (Decarbonization), economic disruption by AI (Digitisation) and wars (De-globalisation) are upon us.

As an extremely open economy, Ireland is likely to catch a cold every time the global economy sneezes. The last thing we should do is take past success for granted. Finite global resources and a relative decline of the West mean we may have to run in order to stand still. There are no free lunches anymore.

Frank Schnittger is the author of Sovereignty 2040, a future history of how Irish re-unification might work out. He has worked in business in Dublin and London and, on a voluntary basis, for charities in community development, education, restorative justice and addiction services.

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.