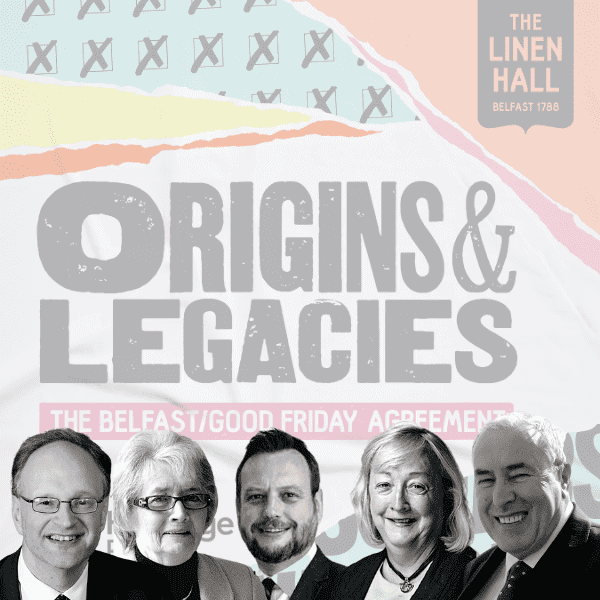

As part of its Origins & Legacies: The Belfast/Good Friday Agreement project at the Linen Hall Library, some of the protagonists of the negotiations from across the political spectrum shared their insights at The Origins of the Agreement event. The panellists were: Gary McMichael; Monica McWilliams; Bríd Rodgers; Peter, Lord Weir; and Mitchel McLaughlin. The conversation was chaired by Mark Simpson, political correspondent for the BBC at the time of the agreement of the peace accord.

The library’s chief executive, Julie Andrews, welcomed the audience, and Mark Simpson began by asking each panellist how they became involved in politics. Gary McMichael explained that his father was working on how to move loyalism beyond the conflict; after his father’s murder in 1987, he felt the need to pick that up again. Monica McWilliams described how the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition emerged from dissatisfaction of women’s response to the Downing Street Declaration; they wanted to get women at the negotiation table. Lord Weir was described by Mark Simpson as a “career politician” and a “baby barrister”, as a graduate of Queen’s University Belfast when he was in the Ulster Unionist Party delegation during the Multi-Party Talks. Bríd Rodgers described herself as an “accidental politician”, recalling when she asked John Hume what he and the SDLP were doing about a particular situation, and Hume replied, “What are you doing about it?” She joined the party shortly thereafter. Finally, Mitchel McLaughlin explained how, for him, the “tragedy and the agony” of the 1981 hunger strikes informed Sinn Féin’s analysis that a united Ireland would need to be “negotiated among all of the traditions on the island”.

After this warm-up question, Simpson asked the panellists whether they thought, one week before the Good Friday, there would be a peace agreement.

McLaughlin answered, “No.” Rodgers thought we could have the “same old, same old” failure as with previous efforts. Weir, citing the penultimate draft document the previous week, thought an agreement was “very unlikely”. McWilliams said that she felt the need to keep optimistic at the time, so that ordinary people could be responsive to a positive outcome: “It was an opportunity that would not come around again anytime soon.” McMichael thought that the deadline date appeared impossible, but that the final draft document was in the right shape, without detail — sufficient enough to keep all on board: “It was a skeleton of a deal.”

Simpson asked what was the turning point, what “turned the page”?

McMichael replied that from a loyalist perspective, it was ok, enough to proceed: “There was enough pain and gain for all.” He appreciated the difficulty of “emotional issues” of policing, security, and prisoners; but the final draft agreement “was as good as it was going to get”. Weir remarked on the high level of commitment by so many to find a consensual solution. He added that the arrival of Taoiseach Bertie Ahern and Prime Minister Tony Blair motivated participants to do better than a “we tried but failed” result. For Rodgers, the moment of optimism came when Seamus Mallon informed her, “We got power sharing to work.” Echoing Weir, Rodgers added: “The people were so desperate for peace. No one wanted to be the spoiler.” McLaughlin discussed their meetings with loyalist delegates and heeded David Ervine (then leader of the Progressive Unionist Party) and his warning that insisting on a one-year release of prisoners “would drive the Ulster Unionists out”; after consulting with republican prisoners’ families, Martin McGuinness came back with agreeing to a compromise of a two-year release.

“What about the various personalities?” Simpson asked the panellists.

McWilliams said that it was important to have good relations with one or two in every party in the negotiations. And perhaps unsurprising in a relatively less populated place like Northern Ireland, McWilliams had a connection with Sinn Féin’s Pat Doherty: “I had taught Pat Doherty’s wife.” While Rodgers made the understatement of the day — “David Trimble wasn’t easy on relationships” — she described how after time, she was able to speak with the likes of Martin McGuinness, Davey Adams, and Gary McMichael: “I saw people that I didn’t know before in a different light. It was very interesting to see those relationships build up.” McMichael picked up on this:

“Whenever people were spending time together, the people in the process had a better understanding of each other than the people outside trying to understand what was going on… Basically, it was a full-time experience. You got to understand the people who were behind it, and not what was on the TV screen. You got to know what was posture and what was real. You had to understand what was possible, what was acceptable. We had to keep as many people as possible on board, because we knew that each of our groups would have to sell it.”

Weir spoke about Trimble’s personality, praising him for his political and personal bravery. Weir cited faults: Trimble played his cards so close to his chest that a deal was not apparent to the rest of the UUP delegation, and Trimble may have underestimated the political [or as McMichael had put it, “emotional”] issues of decommissioning, prisoner releases, and policing. Nevertheless, Weir said that Trimble was the only one who “could pull it off and have credibility to carry and deliver it”.

Simpson opened up the conversation with the audience. One of the topics discussed was what regrets were there about what was agreed or not in the peace accord. McMichael replied that he knew that much was being “kicked down the road” — all things he said were about how people felt about each other and their experience of coming out of conflict, which might have been addressed if there was more time to develop the sincerity of the other community’s experiences:

“If the DUP hadn’t walked out a year after the talks started, if the IRA hadn’t broken its ceasefire, if Sinn Féin had been in the talks from the start… It was a wasted year; the negotiations took place in the last six months.”

Rodgers remarked that the issue of decommissioning could have been handled better than “they’ll do their best”. McWilliams regretted that her team didn’t push more for electoral reform, akin to the Scotland model of voters choosing half of their representatives from a country list and the other half from a constituency list. Weir said that the agreement’s “constructive ambiguity” was important to get the negotiations over the line, but also hindered its implementation later.

As for panellists’ thoughts about the future, McMichael sees the Belfast/Good Friday Agreement as a higher benchmark:

“Everything that happened before 1998 is never going to happen again… It’s okay to have different aspirations and positions… and where concerns can be dealt with in an absence of violence… What was being dealt with in 1998 was much, much more complex, but the price then was higher… The agreement was made on the basis that we would solve all of [the unaddressed issues] through the Assembly, because the Assembly was where the relationships could continue.”

Similarly, Rodgers quoted Hume, who said that we now have the institutions and tools to build a better future and a new Ireland. But the changes brought in with the 2006 St Andrews Agreement have made this more difficult, because you created “a tribal situation”, with every election as “a tribal fight”:

“So, in order to work the Good Friday Agreement, we need to have political leadership that is prepared to work the actual spirit of the agreement, which is a genuine partnership, accepting our differences, and working together on so many of the common interests which bind us all… I think we have to look at the changes we made which have actually stymied the development of a proper, genuine, trusting relationship.”

Weir said that it was naïve to think the 2006 St Andrews Agreement created a level of tribal politics. He recalled a friend who in 1998 told him that elections would be a battle for communal advantage [within each unionist and nationalist communal bloc]. Weir argued for structures that all communities can support.

McWilliams called out Professor Padraig O’Malley in the audience, reminding the audience that he organised the travel of Multi-Party Talks delegates to South Africa to meet with President Nelson Mandela:

“We were finally able to engage in dialogue outside of [Northern Ireland]. I regret that we didn’t have more of those outside of the combative nature of mainstream politics, that there aren’t opportunities today to engage in that kind of honest dialogue.”

Finally, McLaughlin said that he sees a tipping point now in regard to the constitutional future, and an overdue conversation between unionists and southern Ireland about how the latter have prospered without being discriminated against:

“Sectarianism was baked into this place at the time of partition, and that begs the obvious solution to that problem.”

Perhaps at some point in the future we will need another multi-party retreat away from Ireland for delegates to develop relationships to approach another high-stakes negotiation in a constructive manner.

Cross-published at Mr Ulster.

Peacebuilding a shared Northern Irish society ✌️ Editor 🔍 Writer ✏️ Photographer 📸 https://mrulster.com

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.