Last November marked the 1400th anniversary of the death of Saint Columbanus, the Ulster monk whose missions on the continent have made him the patron saint of all those who now seek to build a united Europe.

Last November marked the 1400th anniversary of the death of Saint Columbanus, the Ulster monk whose missions on the continent have made him the patron saint of all those who now seek to build a united Europe.

This anniversary was marked in various ways on the island of Ireland and in Europe, including a joint BBC/RTE documentary titled ‘Mary McAleese and the Man who Saved Europe.’

The Mary McAleese documentary gave some flavour of the sights and sounds of the present-day landscape where Columbanus established monasteries, admonished chiefs and kings, promoted scholarship, and preached the gospel.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p038w19w

Rev Barry Sloan, a Methodist minister and native of Carrickfergus who has worked in the United Methodist Church in Germany for the last 16 years, also followed the Columbanus trail in the lead up to the landmark anniversary.

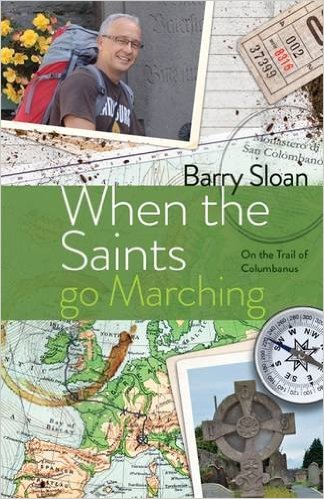

Sloan has chronicled his adventures in a sharp and witty book, When the Saints go Marching: On the Trail of Columbanus (Youcaxton Publications, 2015). [The kindle version of the book is free on Kindle Unlimited.]

Sloan’s journey from Columbanus’ home monastery in Bangor through France, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy is also a journey of inward discovery as he ponders his own identity as a Northern Irish Protestant and how he has come to be open to the spiritual insights of other Christian traditions.

As the first line on the book jacket reads: ‘Why would a Northern Irish Protestant, raised in a staunchly loyalist community, hitchhike through Catholic Europe on the trail of medieval celtic monks?’

The book doesn’t provide much background information about the life experiences that may have pushed Sloan on this journey, but throughout – particularly when he encounters Catholic priests, worship and prayer – he reflects on how these differ from his own tradition and considers what he might learn from them. Near the end of the book Sloan reveals that his father was a ‘Loyalist Prisoner of War’ in Long Kesh, and contrasts his childhood understanding of Protestantism with ‘the expression of true Christian faith and identity in Christ I was later to discover’ (p. 189-190).

One of the more interesting characters he encounters on his way is a monk from Dublin called Patrick who he meets in the Columban monastery in Luxeuil. Sloan details Patrick’s hospitality in hosting him as a guest in the monastery and showing him the Columban sites in the area, as well as noting their theological conversations. Even so, there is a note of sadness when he shares that after discussion with Patrick he did not attend the Sunday service in the monastery church, because of the prohibition on Eucharistic sharing.

Indeed it is the people who extend kindness to Sloan who are the stars of the book, including the members of the Friends of Columbanus, who are scattered throughout the continent. They often serve as impromptu hosts and tour guides.

Then there are those who assist Sloan in his hitchhiking endeavour. For accommodation he relies on internet couch surfing sites, accommodation in churches or monasteries, or people’s homes. Part of the pilgrimage for Sloan is to intentionally trust the providence of God – and/or the kindness of strangers – to deliver him to his destinations along the way.

Sloan recounts a number of humorous and spiritual conversations with these people. His observations about ‘what works’ for enticing people to stop for a hitch hiker are also entertaining – striking just the right look can be challenging and waiting for hours in the sun can sap the spirit.

Sloan supplies plenty of information about the life of Columbanus, providing perspective on his achievements. Readers learn about the strict discipline of the Bangor monks, how they gained the admiration or ire of those on the continent, how Columbanus challenged the temporal power of political leaders, and even Columbanus’ physical exploits – when he was more than 70 years old he set off to cross the Alps on foot to Bobbio in Italy to start a new monastery.

In the final chapter, Sloan uses the German phrase ‘na und?’ (‘and now?’) to focus his reflections. And this chapter becomes a call – to himself and also to his readers – to build a kind of church that reflects the spirit of the ancient Celtic mission in Europe (p. 191):

‘The stories of Columbanus, Gall and the other missionary monks from Bangor have left a mark on me. I know they lived in a different era, and I know their understanding of the Christian faith and how it is practised, differs at various points with mine. But I have nothing but the utmost respect for these men of God who heard the call to follow Christ ‘even unto the end of the world’. I admire their dedication, their faith, their intellect and the way they integrated their faith into everyday life. For them, there was no sacred and secular, for all was holy, if submitted to God.

My Columban adventure has convinced me more than ever that modern day Europe needs this kind of church. … A church that is more a movement, than a monument – always reforming, and breaking down walls, crossing borders as it reaches out to others in love.’

Gladys is a Professor of Sociology at Queen’s University Belfast and a member of the Royal Irish Academy.

She is also a runner who has represented Ireland and Northern Ireland. She blogs on religion and politics at gladysganiel.com

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.