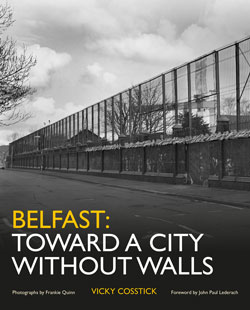

In certain parts of Belfast, walls dominate the landscape – as well as the consciousness – of those who live and work around them. A new book by Vicky Cosstick, Belfast: Toward a City Without Walls, explores the history, significance and most daringly, the future, of these walls, highlighting the efforts of some citizens of the city to transform the conflict that produced them.

In certain parts of Belfast, walls dominate the landscape – as well as the consciousness – of those who live and work around them. A new book by Vicky Cosstick, Belfast: Toward a City Without Walls, explores the history, significance and most daringly, the future, of these walls, highlighting the efforts of some citizens of the city to transform the conflict that produced them.

Cosstick, who lives in London and Ireland, is a journalist who has also worked as an academic and organisational change consultant. Her interest in the walls was aroused in 2013 when researching articles on the 15th anniversary of the Belfast Agreement. During this time, the Office of the First Minister and Deputy First Minister (OFMDFM) released its Together Building a United Community (TBUC) document, which pledged to bring down the walls by 2023. For Cosstick, this signalled that a deeper investigation of the walls was necessary.

This book is a result of that investigation and Cosstick’s collaboration with photographer Frankie Quinn, who is from Short Strand. Quinn’s striking black and white images illustrate the book, providing a powerful visual witness of the impact of the walls on the city.

Cosstick examines the walls from multiple angles, with chapters on their history, as well as on dialogue and regeneration in the communities around the walls, former paramilitaries and youth, the churches and Christian activists, arts and architecture, and business and tourism.

In the process she provides a variety of perspectives from those whose lives and work are impacted by the walls, skilfully tying their stories together. She spoke to more than 100 people directly involved. In his forward to the book, prominent academic John Paul Lederach describes it this way, and I concur:

‘Vicky Cosstick has woven a web of a good book. I read these pages once and then a second time, slowly. The reading merits the spider’s approach – forth and back, criss-crossing the same space differently each time, sort of the way Vicky wrote the book I imagine, following wall-strand stories.’

As is well-known, Belfast has more than 100 walls and interfaces and their number has increased since the Belfast Agreement. These facts, needless to say, are not encouraging for those who are working for conflict transformation. But Cosstick admits she takes a relentlessly optimistic view in the book:

‘This book is written from a ‘peace’ perspective and from a generally positive point of view. It assumes that, by whatever uncertain and circuitous route, the peace process is advancing – an assumption further supported by the reaching of the Stormont House Agreement in December 2014. The book aims to accompany and echo the doggedly persistent work of the many people and groups whose lives and work are defined by the walls and interfaces, to give a real time picture of the complex process by which constructive change is being worked out in the life of the city’ (p. 23).

And it is indeed people’s stories that make up the heart the book, providing examples of hope that are usually obscured by lack of progress at Stormont or the visible signs and symbols of sectarianism in communities. Quinn’s photographs also support the theme of hope; for example, ‘before’ and ‘after’ photos of the Workman Avenue Gate illustrate how the walls are in some cases changing gradually over time and becoming less foreboding.

In a Question and Answer session about the book during February’s 4 Corners Festival, Cosstick spoke about the ‘Our View’ project, facilitated by artist Rita Duffy and youth worker Rory Doherty, which featured the stories and artwork of 21 young people from north and west Belfast. This is just one of many stories throughout. Given my own research on and interest in the churches and Christian activism, I was drawn to the stories in Chapter 5, ‘Maverick Ministries: The Churches.’

Cosstick shares the assessment of academics John Brewer, Gareth Higgins and Francis Teeney’s book, Religion, Civil Society and Peace in Northern Ireland that while the institutional churches could have done more, it was brave ‘mavericks’ operating outside the institutions of the church who carried – and continue to carry the load – in peacebuilding. She also features the 4 Corners Festival, as well as the work of individual clerics and activists.

But what jumped out at me from the chapter was the text of a homily by Fr Tom Toner, who is now deceased, which was preached on 20 March 1988 in St Agnes Church the Sunday after two British corporals were murdered after driving into the funeral of those killed in Michael Stone’s attack on Milltown Cemetery.

Toner’s homily, of course, does not deal directly with the book’s theme of bringing down the walls. But what Toner said seems to me a striking example of the type of courage and self-awareness needed by those living near the walls to finally remove them:

‘I bring to the altar this morning the pictures of the half-naked battered bodies that I saw lying in the waste ground; you bring the TV pictures of savage behaviour, some of you bring eye witness memories of that savagery. We bring these and all the feelings and reactions that accompany them to our Eucharist where we commemorate the battered body on the Cross of Jesus. We bring to the altar our shame, our fear, and any guilt we feel for what was done in our parish. We bring too the hatred, anger and rage that caused people, Catholic people, to behave as they did.

… it was hard to find the face of Jesus here yesterday. But I did find it – in the dead bodies that were sacrificed on the altar of hatred, revenge and fear. I found his face in the faces of women who wept at the memory of what the saw at Casement Park and I thought of the words of Jesus to the women: “Weep not for me but for yourselves ad for your children.” I found it in the drawn face of the priest who tried to prevent the murder and ministered to the dead.

There was a parody on the Stations of the Cross out there, even to the stripping of the victims. The 10th Station will never be the same for me again: “Jesus is stripped of his garments” (p. 118-119).

Beyond the stories and the examples, Cosstick also offers some analysis of how the walls are currently used – i.e. not just for safety and separation but also for tourism. She acknowledges that conflict-related tourism can be partisan and divisive, as well as insensitive to people who live near the walls, yet points to the Crumlin Road Gaol as an example of the transformative potential of some conflict-related tourism.

And Cosstick also offers some insight on the eight International Fund for Ireland funded programmes in particular parts of Belfast and Derry. Cosstick interviewed people involved with all eight of the programmes and reports on what has happened. She is encouraged that these workers have taken a holistic and contextual approach, seeing broken relationships and socio-economic deprivation as problems to be tackled along with the physical presence of the walls (p. 60-61). It is worth quoting at length Cosstick’s assessment of these programmes, as there has been so little in the public domain about them:

‘IFI has invested £4 million over 2-3 years in the initial phase of these peacewalls programmes, due to end by August 2015. By then the work will be far from complete – although IFI recognised that to begin with the work was all about starting to create the conditions for the removal of the peacewalls. Even part-way through it is clear that the eight programmes have been effective and are likely to merit continued funding. It is also likely that the ‘IFI model’ will be replicated in other interface areas.

… There were a total of 91 barriers and 139 objectives, across the two cities, included in the eight projects and by late 2014, 39 objectives had already been achieved’ (p. 65-66).

Cosstick points out that the IFI programmes were set up before the flag protests and Twaddell dispute, which have slowed progress in Belfast. But progress has been made nonetheless. She also notes that the Irish Government has now given the IFI a further €5 million to implement phase two of the programme (p. 176). And she recognises that while OFMDFM and TBUC promise to bring down the walls, they have no mechanisms for doing so, and hence are de facto relying on the IFI programme and the owners of the walls (the Housing Executive and other bodies) to actually bring them down. Finally, she raises the question of whether the British government should stump up the money for their removal.

It is already reasonably clear from the optimistic examples Cosstick profiles in the book that she can envision a city no longer hemmed in by the walls that have shaped it for a generation. Yet still she warns (p. 180): ‘Anger, cynicism and apathy have the power to constrain peacebuilding efforts if allowed.’

It’s up to the peace of Northern Ireland not to allow it.

Belfast: Toward a City Without Walls is available for a reasonable £15 from Colourpoint.

Gladys is a Professor of Sociology at Queen’s University Belfast and a member of the Royal Irish Academy.

She is also a runner who has represented Ireland and Northern Ireland. She blogs on religion and politics at gladysganiel.com

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.