On Wednesday evening, Professor Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke from All Souls College, Oxford delivered the annual Donal Nevin lecture in Queen’s University’s Canada Room.

On Wednesday evening, Professor Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke from All Souls College, Oxford delivered the annual Donal Nevin lecture in Queen’s University’s Canada Room.

Organised by the Nevin Economic Research Institute (NERI), the lecture is held in honour of the former General Secretary of the ICTU. He was a trade unionist and a historian committed to ending poverty and the promotion of social justice. The inaugural lecture was given by President Michael D. Higgins in 2013. The annual event alternates between Dublin and Belfast.

You can listen back to O’Rourke’s talk along with Dr Katy Hayward’s response and the Q&A.

While the organisers had an idea of where in the Brexit negotiation process the UK would be when the lecture was scheduled, they had no idea that their guest would be speaking while Conservative MPs were voting on the future of their party leader. O’Rourke promised to “talk about what has happened in the past and how we got where we are today” rather than what is going to happen in the next weeks and months.

“My firm belief is that you understand where we’re at, not just why Brexit happened but why the negotiations have gone in the way that they did, if you know a little bit of history.”

His book Une brève histoire du Brexit – “written by an Irishman about Brexit for a French audience!” – is being published in English in the new year as A Short History of Brexit: From Brentry to Backstop.

His book Une brève histoire du Brexit – “written by an Irishman about Brexit for a French audience!” – is being published in English in the new year as A Short History of Brexit: From Brentry to Backstop.

In July, Jacob Rees-Mogg warned Theresa May that that if she didn’t watch out she would suffer the same fate as Robert Peel back in 1846. Back in 1961, Harold Macmillan feared the same when he performed his U-turn on the UK and Europe and felt backbenchers getting twitchy.

O’Rourke reminded his audience that in the 1800s, the Tories were the party of aristocratic landlords with a vested interest in high food prices, while the Liberals wanted free trade. While “a belief in free trade became part of the religious political orthodoxy in London, there are always some Conservatives who remain sceptical and we get periodic eruptions”.

In 1881, the Fair Trade League was formed to address a perception of unfairness with trade and a desire to put tariffs on imports. The league “didn’t think that the UK should sign up to trade deals unless they would be terminable at a year’s notice, so they wanted the right always to be able to get out of any deal without entanglements”. Tariffs would be place on ‘foreign’ food, but not that imported from the British Empire. The 1885 election was fought between free-traders and fair-traders.

Later ‘Imperial Preference’ emerged, supported by Joseph Chamberlain, to allow the duty free import of goods from Empire countries, but tariffs for everyone else.

“The Tory party has a history when it comes to the question of how Britain should deal economically with foreigners. But the EU also has … a very specific history, and the institutional shape of the EU, the way that the EU thinks about policies, and the way that the EU is reacting to Brexit all reflect that history.

“The most obvious thing say about the EU is that its history in large part reflects the two World Wars. That’s an argument to which many people in Britain have often been allergic.”

O’Rourke went on to explain that “the EU is supranational, and that’s what the Brits have never liked”. Free trade is great but why do we need the Commission, or the Court of Justice. Why all these constraints and collective decision-making? Why risk being in a minority on a decision that we might care about?

O’Rourke went on to explain that “the EU is supranational, and that’s what the Brits have never liked”. Free trade is great but why do we need the Commission, or the Court of Justice. Why all these constraints and collective decision-making? Why risk being in a minority on a decision that we might care about?

The EU is supranational in a way that NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Association) is not, with none of the “paraphernalia we have in Europe”.

Europe has been in decline since the turn of the 20th century. He reckoned Maurice Faure was quite prescient when on 5 July 1957 he said:

“You see, my dear friends, we still maintain the fiction that there are four Great Powers in the world. Well, there are not four Great Powers, there are only two: America and Russia. There will be a third at the end of the century: China. And it is up to you as to whether or not there will be a fourth: Europe.”

On top of these geopolitical aspects, O’Rourke argued that there were also domestic policy reasons why European integration was supranational.

“Europe reacted to the disaster of the 1930s, the Great Depression and the rise of nationalism with Keynesian macroeconomics to stabilise economies. It needed welfare states so you didn’t have people on the streets of Berlin if they lost their jobs getting ever more radicalised. Growth strategies were put in place that involved what 1990s’ Ireland called social partnership, the rest of Europe did that in the 1950s and 1960s. There were bargains where the workers moderated their wage demands and then in return the employers invested the resulting profits in local industry, thus providing jobs and growth.”

He went on to explain the choice facing European countries.

“There’s no country in Europe that’s going to have a free trade deal that doesn’t involve agricultural interest being protected [to] keep prices high. You can either have free trade in industrial goods only, and countries all keep their own agricultural policies, or you can have free trade involving everything, but then instead of having national agricultural policies, you have to have a European agricultural policy.

“An industry-only free trade deal was never going to work because countries like Italy, France or the Netherlands wouldn’t have had a lot to gain … so you were immediately pushed into a situation where a European-wide free trade deal had to involve agriculture, a common agricultural policy, and supranational decision-making structures to determine the level of price support.

“They decided after the disaster of the interwar period that they have to have free trade at the level of Europe, but that that free trade couldn’t come at the expense of these nascent welfare states and mixed economies. You had to have free trade, but you had to stop destructive regulatory races to the bottom.”

O’Rourke explained how the Treaty of Rome built in protections for matters already enjoyed in certain countries (like France’s equal pay for men and women) while adding safeguards if other countries didn’t fully adopt them despite the treaty’s requirement that they “endeavour” to do so.

“The original raison d’être of the EEC as it was is to combine the continent-wide effects of free trade with the prevention of risk destructive regulatory races to the bottom.

Joseph Chamberlain’s son Neville became Chancellor in November 1931 and immediately introduced Imperial Preference. This switch to protection “is overwhelmingly against foreign goods not against British Empire or British Commonwealth goods. Coinciding with that switch there is a big increase, as you would expect, in the share of British imports coming from the Empire.”

“In 1941, Roosevelt’s not at war yet but he soon will be. When Winston and FDR meet off the coast of Newfoundland they issue the Atlantic Charter, an eight-point plan … the grand geopolitical war aims of the what will soon become the Allies.”

Allies will post-war get access on equal terms to the trade and raw materials they need. Imperial preferences will be replaced with non-discriminatory trading, built into Article 1 of GATT. There were some exceptions and one of those allows forming customs unions and O’Rourke explained the differences between free trade areas and customs unions: “with free trade areas you always have checks at the border to check [whose beef it is]”.

By 1947 the British Civil Service are thinking about European integration and …

“they say it had nothing in its favour other than the damage that will be caused by being excluded from it, which I think sums up perfectly a certain type of British attitude towards European integration!”

‘Plan G’ was proposed which managed to satisfy all of Britain’s red lines.

“They would have an industrial free trade area only, industrial goods only, with all of Europe all of the OEEC including the European Union. This is brilliant because it meant they could continue to export industrial goods to the new EEC. It meant that they wouldn’t have to include agriculture [and] could continue to have their own agricultural policies which were very different, and could continue to have their own free trade deals with the Commonwealth.

“From a British point of view this is brilliant, but they forgot that they had negotiators on the other side who have their own interests and from the point of view of the French or Dutch or Italians there was nothing to like here because they were trying to sell agricultural goods.

“So this was never going to fly. But they were so fixated on what would work in London that they completely forgot what would be required to do a deal with the other side. They were very optimistic going in [about being] able to do this on our own terms.”

Sound familiar?!

Benjamin Grob-Fitzgibbon summed it up in 2016: “Under its terms, the British government could have its cake and eat it, too, aligning itself with its European neighbours without in any way distracting from its Commonwealth relations”.

The UK stays out, but British GDP per capita declines relative to France and Germany. But “they want to be exposed to German competition to force [UK] businesses to up their game”.

By 1960, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan had formed the European Free Trade Association (though France blocked his government’s 1963 application to enter the EEC).

O’Rourke fast forwarded to Margaret Thatcher’s premiership.

“If you want to get rid of physical barriers, ie border controls, you have to get rid of the technical barriers [eg, mismatching safety regulations] to trade and the fiscal barriers [eg, VAT] to trade that require those border controls.”

Thatcher’s right hand man and one-man thinktank Arthur Cockfield in 1985 “basically says … these barriers cost time and money”.

“It’s a very pragmatic Anglo-Saxon reason for having common rules and regulations. And the good news is the thanks to Northern Ireland and the protocol we now a very handy list of all of the rules and regulations that you need to keep trade frictionless and to avoid barriers at borders. They’re contained in a 69-page Annex 5 of the Northern Irish Protocol and you can just point and click and see what all these regulations are.”

O’Rourke reminded the audience that “the EEC, or the EU as it now is, it’s only a bunch of treaties”.

“The only thing that makes the EU the EU is the treaties and the fact that they’re respected.”

It’s very good for the EU that it controls its own rules … if you’re a company no matter how big no matter how powerful … if you want to play in our market you play by our rules. That’s the only bit of significant power I think that Europe has at the global level. We’re not a military power; we’re not a foreign policy player – we’re all over the place in foreign policy – but this is real power. So they’re not going to give up this. So they’re not going to have a situation where the British government tell them what they can and can’t do with their own rules. That’s just so simple self-preservation.”

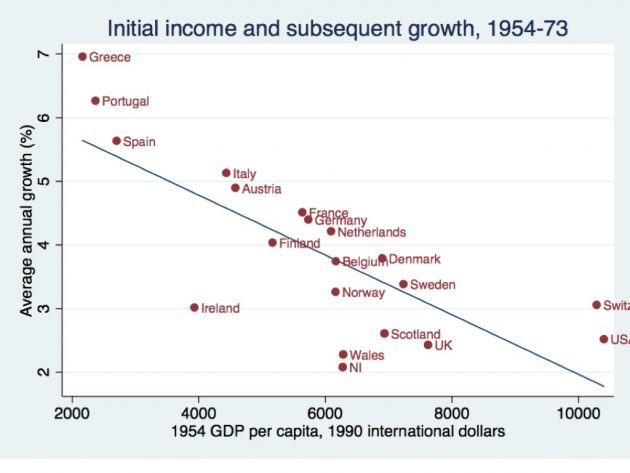

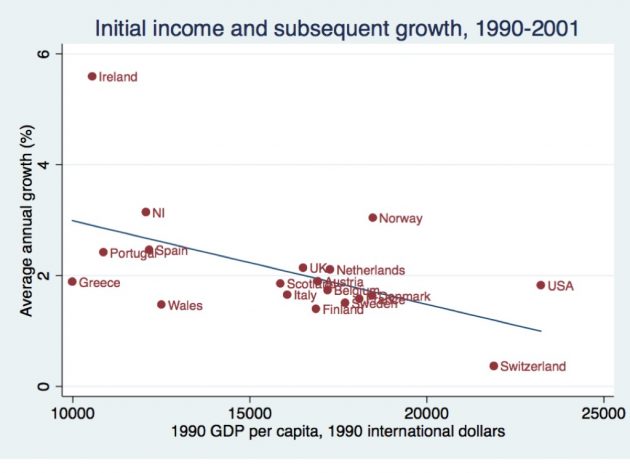

O’Rourke switched to Irish economic history and pointed out through a series of charts that there was “a convergence of poor countries growing (in terms of GDP per capita) more rapidly than rich countries”. Throughout the 1950s, Ireland was poor and should have been growing at Italian rates. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as well as the UK as a whole are in a similar position to Ireland, behaving like one big ‘British and Irish’ economy.

O’Rourke switched to Irish economic history and pointed out through a series of charts that there was “a convergence of poor countries growing (in terms of GDP per capita) more rapidly than rich countries”. Throughout the 1950s, Ireland was poor and should have been growing at Italian rates. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland as well as the UK as a whole are in a similar position to Ireland, behaving like one big ‘British and Irish’ economy.

Ireland only stopped underperforming after 1973 (when they joined the EEC). Their economy decouples from the UK and their growth between 1973 and 1990 is good, but nowhere near as good as between 1990 and 2001.

Ireland only stopped underperforming after 1973 (when they joined the EEC). Their economy decouples from the UK and their growth between 1973 and 1990 is good, but nowhere near as good as between 1990 and 2001.

“I think from an Irish point of view, our independence would never have worked as well as it did without EU membership. Our EU membership would never have worked as well as it did without independence. So for us, the two things have always complemented each other, not just economically but politically as well because it gave us a place around the table that we didn’t have before.”

O’Rourke suggests that to understand Brexit and the negotiations that follow, you need to understand the three histories (UK, EU and Ireland) and how they have shaped attitudes and economies, and how they are interacting today as well as the logic of free trade areas vs customs unions vs single markets. He argues – and writes in his book – that “a lot of what we have lived through during the course of the last two and a half years follows fairly logically from this”.

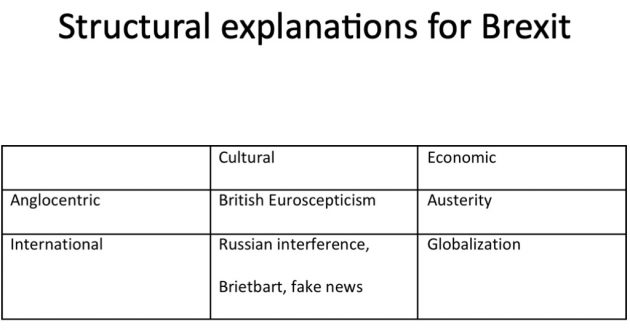

He finished with a short discussion around the structural causes of Brexit and the different arguments around cultural and economic reasons. Focussing on Britain, it could be blamed on the Tory party’s “nostalgia for the Empire”. Or you can imagine an Anglo-centric economic argument around George Osborne’s austerity packages.

He finished with a short discussion around the structural causes of Brexit and the different arguments around cultural and economic reasons. Focussing on Britain, it could be blamed on the Tory party’s “nostalgia for the Empire”. Or you can imagine an Anglo-centric economic argument around George Osborne’s austerity packages.

“You can’t think about Brexit in isolation. It happened in the same year as Donald Trump. The next year you have the French National Front almost making it to the second round. You had the Austrian SPÖ making it into government as part of a coalition …

“[So] the polar opposite option is an argument that says this is nothing to do with Britain. It is to do with how this country is responding to the same globalisation-related shocks as Trump’s Heartland and the formerly industrial parts of France.”

In 1999, O’Rourke co-authored a book with Jeffrey Williamson about the anti-globalisation of the late 19th century in which they – perhaps prophetically – said:

“Politicians, journalists, and market analysts have a tendency to extrapolate the immediate past into the indefinite future, and such thinking suggests that the world is irreversibly headed toward ever greater levels of economic integration. The historical record suggests the contrary … unless politicians worry about who gains and who loses, they may be forced by the electorate to stop efforts to strengthen global economy links, and perhaps even to dismantle them.”

O’Rourke looked beyond the UK’s borders and commented:

“It’s important that Europeans not be too superior about the problems that Britain is going through right now. I was living in France in 2005 in this little village during the French referendum campaign on the Constitutional Treaty … The thing was voted down and there was a very very clear class divide: 35% of professionals vote No, 79% of blue collar workers vote No.”

There was a similar class divide in the Republic of Ireland’s vote on the Lisbon Treaty a few years later and O’Rourke argues that “this is just a British story: it’s a very basic, general story that all of our democracies have been going through”.

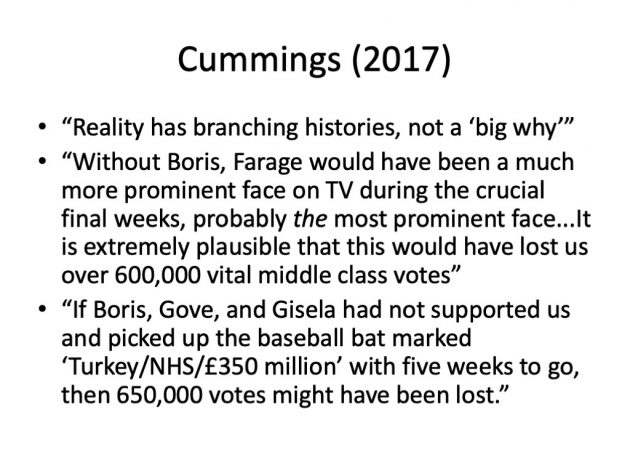

O’Rourke finished by referring to “an absolutely brilliant blog post by Dominic Cummings”, the mastermind behind Vote Leave.

O’Rourke finished by referring to “an absolutely brilliant blog post by Dominic Cummings”, the mastermind behind Vote Leave.

“It’s a very honest and insightful blog post about how the referendum was won from his point of view. He has one line that expresses what I want to say beautifully.

“He says in history there are no big ‘why’s. It’s all about branching histories … Well, tonight, isn’t it obvious that it could branch in many different ways. And it’s very little factors, small margins that are needed to branch one way or the other.

“So, for example, he talks about Boris Johnson’s last minute decision to campaign for [leave] rather than [remain]. If it hadn’t have been Boris heading up the leave ticket, it might have been Nigel Farage that he thinks probably would have scared off lots of middle-class voters.

“You also want to think about the context. 2015/16 is a terrible year at to be trying to convince people to stay in the European Union because there’s a migration crisis which is a real crisis and it’s a complete shambles.

“And there’s the Eurozone crisis which had been ongoing for a long time already and was also a complete shambles. At that stage the British economy had recovered from the crisis because the bank of England had done the necessary, Osbourne wasn’t helping but the bank was doing what it had to do. America had recovered a lot earlier because the bank was doing what it needs to do there and Obama was stimulating the economy. The Eurozone had slammed on the fiscal breaks in 2010 and the ECB was always much too conservative.

“So it is easy then to argue that the EU is a club that you shouldn’t be scared to leave.

“If I was teaching a class in 50 years time and we were asking why did Brexit happen, I would talk about those structural factors. I’m enough of an economist and a social scientist to believe that structure matters, but because I’m also an economic historian, I also believe that chance and contingency matters …

“What history tells you is that we were all endowed with freewill and so are our leaders and the choices that people make for better or for worse end up really mattering and that nothing is preordained and that’s not a bad thought to keep in mind in dangerous times.”

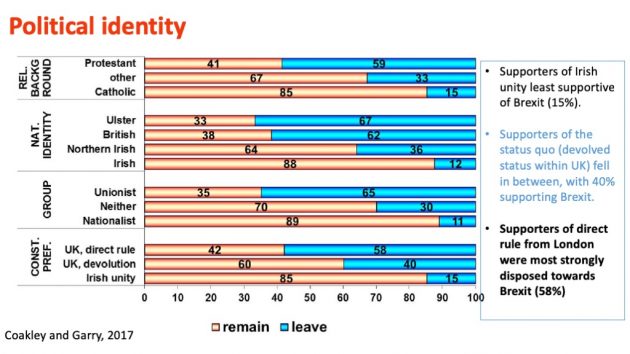

Dr Katy Hayward from QUB’s Mitchell Institute responded to the O’Rourke’s address by providing the Northern Ireland context around anti-globalisation and how it affected attitudes towards leaving the EU and the value of immigration.

Dr Katy Hayward from QUB’s Mitchell Institute responded to the O’Rourke’s address by providing the Northern Ireland context around anti-globalisation and how it affected attitudes towards leaving the EU and the value of immigration.

She reminded the audience about the correlation between religious, national and political identity, as well as constitutional preference, with how people voted in the EU Referendum to remain or leave.

There was a reminder of the considerable convergence and coalescence of Northern Ireland political opinion – or common ground – around Brexit threats, right up to the point they diverged when the constitutional question came to the fore.

There was a reminder of the considerable convergence and coalescence of Northern Ireland political opinion – or common ground – around Brexit threats, right up to the point they diverged when the constitutional question came to the fore.

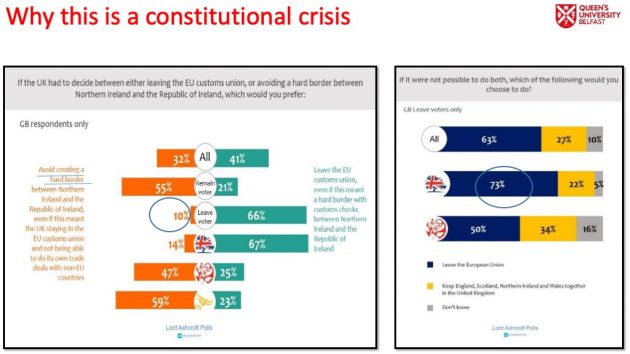

Using a Lord Ashcroft poll, she demonstrated the constitutional crisis with GB Tory supporters overwhelmingly preferring to leave the EU customs union rather than avoiding creating a hard border between NI and ROI.

Three quarters of GB Tory-supporting Leave voters would put leaving the EU above keeping the four nation Union intact.

Hayward grouped the myriad of possible options into three scenarios:

- No Brexit – with flux (eg, General Election) now, but longer term stability;

- Withdrawal Agreement – stability now, but longer term flux; and

- No Deal (chaos followed by flux).

She said that no matter how people voted in the EU referendum, they are faced with flux.

During the Q&A chaired by the BBC business journalist Clodagh Rice, NERI’s director Dr Tom Healy recalled that just a week ago, Theresa May had stood in the lecture venue, QUB’s Canada Room. She might have preferred to be back rather than awaiting her party MPs’ votes in Westminster.

During the Q&A chaired by the BBC business journalist Clodagh Rice, NERI’s director Dr Tom Healy recalled that just a week ago, Theresa May had stood in the lecture venue, QUB’s Canada Room. She might have preferred to be back rather than awaiting her party MPs’ votes in Westminster.

May probably has no time to think how historians will view her 50 years from now However, is she aware of her party’s long perturbational history of trading with other European nations? And is she cognisant of the changing attitude towards globalisation that may be driving how the public – and MPs – will vote in coming weeks and months?

Alan Meban. Tweets as @alaninbelfast. Blogs about cinema and theatre over at Alan in Belfast. A freelancer who writes about, reports from, live-tweets and live-streams civic, academic and political events and conferences. He delivers social media training/coaching; produces podcasts and radio programmes; is a FactCheckNI director; a member of Ofcom’s Advisory Committee for Northern Ireland; and a member of the Corrymeela Community.

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.