The Insurrection in Dublin during Easter 1916 involved less than 1,700 men and women. It was the brainchild and initiative of a minority, of a minority of a minority- a small conspiratorial grouping within the leadership of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, who had itself been using and manipulating the Irish Volunteers behind the scenes, who in turn had themselves broken away from the populist Irish (later renamed the Irish National) Volunteers. A group of self-indulgent individuals unrepresentative of Irish society in terms of class or political aspiration, and indifferent to that reality.

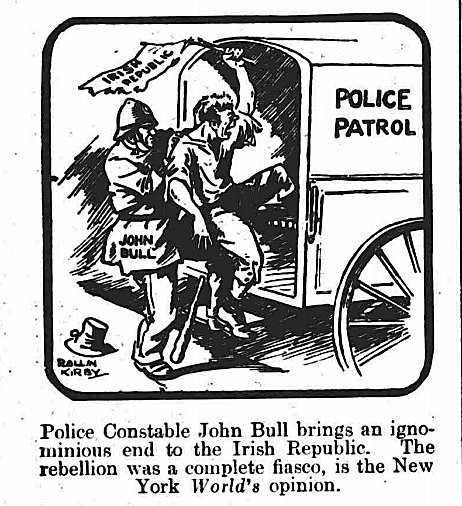

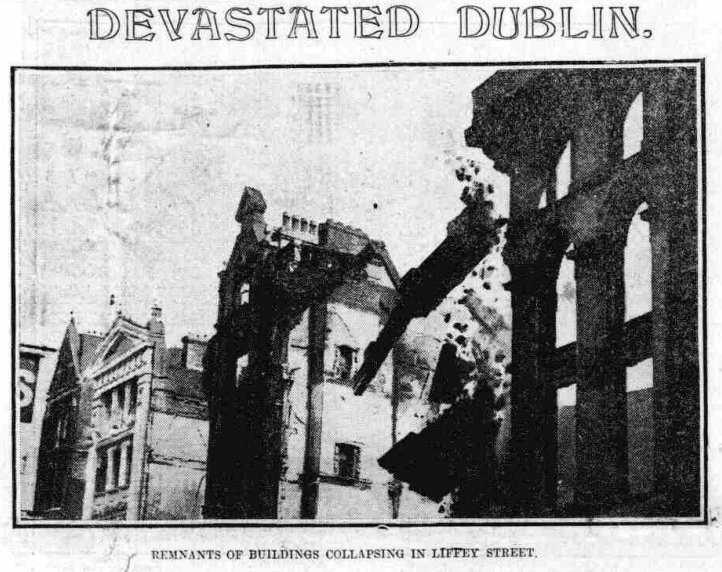

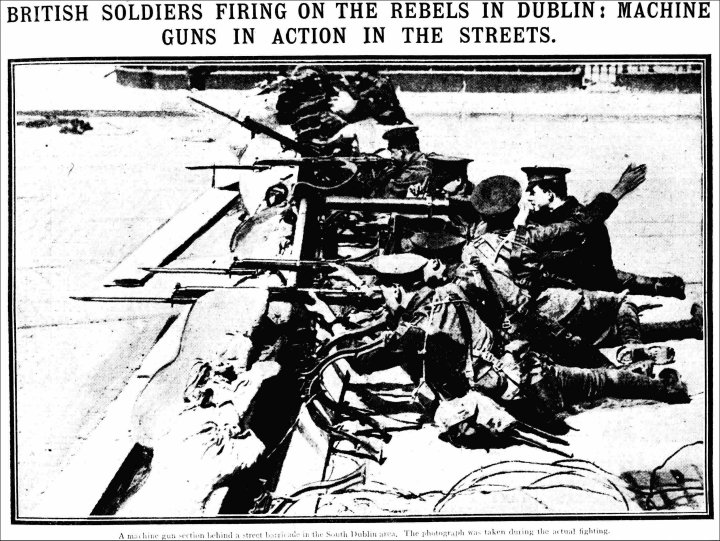

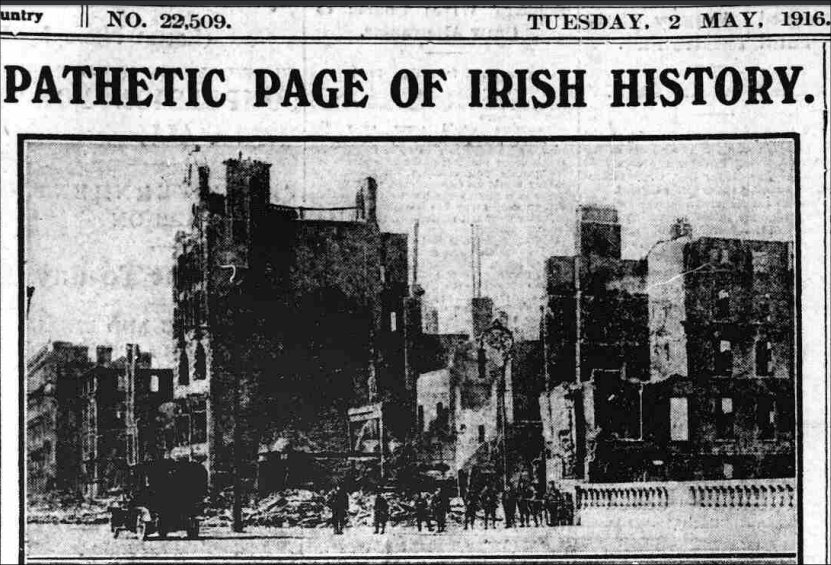

When Patrick Pearse read the personally penned Proclamation of the Irish Republic on the 24th of April, while civilians self-styled as ‘Volunteers’ of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army occupied prominent public buildings, the British army was indeed caught by surprise. Once that surprise had settled however, its personnel very quickly quelled and then crushed the insurrectionists. The unqualified defeat of the rebels did not take place nevertheless until the events they had initiated took the lives of almost 500 men, women and children; injured in excess of 2,000; and created damage and loss to Dublin City amounting to over £3 million pounds (a modern equivalent of between approximately £180 and £300 pounds). In purely military terms their actions had been an absolute and resounding failure.

When Patrick Pearse read the personally penned Proclamation of the Irish Republic on the 24th of April, while civilians self-styled as ‘Volunteers’ of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army occupied prominent public buildings, the British army was indeed caught by surprise. Once that surprise had settled however, its personnel very quickly quelled and then crushed the insurrectionists. The unqualified defeat of the rebels did not take place nevertheless until the events they had initiated took the lives of almost 500 men, women and children; injured in excess of 2,000; and created damage and loss to Dublin City amounting to over £3 million pounds (a modern equivalent of between approximately £180 and £300 pounds). In purely military terms their actions had been an absolute and resounding failure.

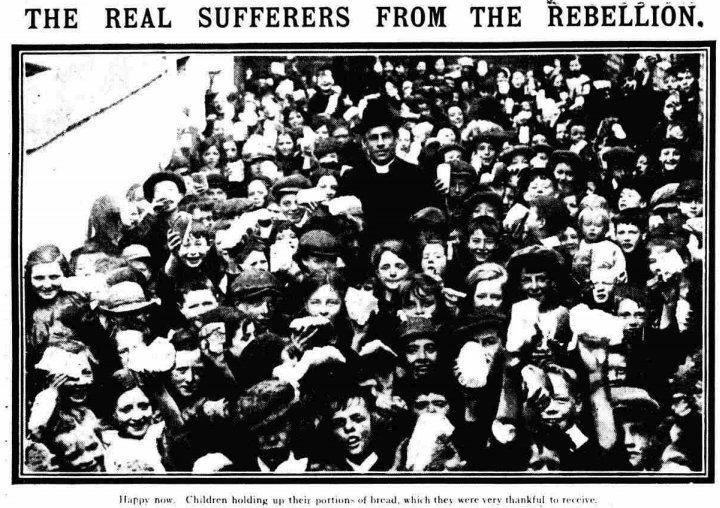

Over and above modern political interpretations and hindsight opinion and thought, the one indisputable thing that the Rebellion delivered is death. The specific causes of each individual death are in many ways irrelevant. They died. The definitive figures now accepted are that 485 people lost their lives during the disturbances. Over half were civilians caught in the crossfire, with the last day alone seeing 45 deaths of non-combatants. Ordinary men and women, Catholic and Protestant, caught up in the middle of a Rebellion they knew nothing about and most would likely have had little affinity with. The more horrifying statistic is that among their number 38 of the dead were under 16 years of age. Men, women and children who had their life extinguished to placate ideological and borderline fanatical desires of a tiny few.

On the cusp of the Great War, commentary on the Irish situation had all but come to the conclusion that civil war was not just possible but inevitable; reinforced by sources within the intelligence ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary. In July 1914 the RIC Inspector for County Cavan commented on UVF and Irish Volunteer activity that the ‘outlook is dangerous’; while in nearby Monaghan, his equivalent stated in his July report that between the two parties ‘danger of collision is considerable’. Whilst the Ulster Volunteers had no presence in much of the South and West of Ireland (there were some pockets of anti-Home Rule Volunteers in Dublin, Cork, Wicklow, Sligo, Longford, Leitrim and Louth); potential battle-lines were being suggested. George Berkley, an Irish Volunteers commander in Belfast, related how a Southern Home-Ruler had asserted that ‘For every Catholic shot by the Orangemen in the North, I’ll get five Protestants down here’.

On the cusp of the Great War, commentary on the Irish situation had all but come to the conclusion that civil war was not just possible but inevitable; reinforced by sources within the intelligence ranks of the Royal Irish Constabulary. In July 1914 the RIC Inspector for County Cavan commented on UVF and Irish Volunteer activity that the ‘outlook is dangerous’; while in nearby Monaghan, his equivalent stated in his July report that between the two parties ‘danger of collision is considerable’. Whilst the Ulster Volunteers had no presence in much of the South and West of Ireland (there were some pockets of anti-Home Rule Volunteers in Dublin, Cork, Wicklow, Sligo, Longford, Leitrim and Louth); potential battle-lines were being suggested. George Berkley, an Irish Volunteers commander in Belfast, related how a Southern Home-Ruler had asserted that ‘For every Catholic shot by the Orangemen in the North, I’ll get five Protestants down here’.

The War changed that instantaneously. Perhaps because of the conscious or even sub-conscious knowledge that it was an opportunity to step back from ‘the brink’ without loss of face, throughout Ireland the War effort was embraced across creed and class boundaries. The numbers involved are debated, but over 200,000 Irishmen fought in the War, while as many as 49,000 died, depending on the criteria used to define what was an ‘Irishman’. They enlisted for many different reasons. Some did so for Ulster, while some did so for Ireland. Others joined to make sure their wives and families would be provided for, others still to escape heavy laborious work in mills and factories. Some through peer and community pressure, and some simply joined for adventure. For all the reasons why were less relevant to both the men and to their families, than the simple fact they were physically ‘at War’, or dealing with the absence of those at War.

Within this specific context the Rebellion instantly generated a hatred and anger among hundreds of thousands, if not millions of Irishmen and women. Individuals who felt a deep resentment that these people in Dublin should countenance such actions whilst their loved ones were in far off fields fighting and dying for the good of Ireland and for Ireland itself. This was not just a Rebellion, it was a mutiny.

On the 27th April on the fields of Hulluch Northern France, the 16th Irish Division found themselves on the end of a German gas attack. Just one of many events on the fields of the Battle of the Great War that week; in that one incident, the 16th Division lost 442 men, almost to a man Irishmen. Their deaths having taken place while the Easter Rebels were proudly emphasising they were supported by, and they de-facto returned support to, the perpetrators- people the rebels described as their ‘gallant allies’.

During the Rebellion men from the Reserve of the 36th Ulster Division also traveled south to support the forces engaged in quelling the trouble. Several would die. Of the British soldiers killed in the execution of their duty during Easter Week in Dublin, 22 were Irishmen. As aforementioned, not much less than a quarter of a million fought in the Great War. About 1,600 men and women took part in the Easter Rebellion.

At Easter 1916 a 38 year East Belfast man and his brother traveled to Dublin. James and Joseph Mitchell visited the Theatre Royale to watch a show, attended a function in local military Barracks, and on Easter Sunday James completed what he had visited Dublin for in the first place, he enlisted in the British army. On Easter Monday the brothers attended the races at Fairyhouse, where they became aware of the disturbances in the City, and shortly after found themselves confined to the Gresham Hotel. James kept a diary of events in the week to follow. As the Rebellion was coming to a close he penned a sentence that adequately reflected the opinions of those disgusted at the timing of the affair, ‘I felt relief and secretly exalted at the inglorious end of the creatures with such… selfish minds’.

At Easter 1916 a 38 year East Belfast man and his brother traveled to Dublin. James and Joseph Mitchell visited the Theatre Royale to watch a show, attended a function in local military Barracks, and on Easter Sunday James completed what he had visited Dublin for in the first place, he enlisted in the British army. On Easter Monday the brothers attended the races at Fairyhouse, where they became aware of the disturbances in the City, and shortly after found themselves confined to the Gresham Hotel. James kept a diary of events in the week to follow. As the Rebellion was coming to a close he penned a sentence that adequately reflected the opinions of those disgusted at the timing of the affair, ‘I felt relief and secretly exalted at the inglorious end of the creatures with such… selfish minds’.

Ireland’s religious divisions and boundaries have rarely been far from the surface since the Reformation, and the Third Home Rule Crisis had once again elevated them to a position of eminent importance. Rightly or wrongly, one of the central tenants of Irish Unionist objections to Home Rule was a fear of the Catholic Church. Fears that freedom of religion, of expression and even simply their individualism would be taken away from them in a Catholic dominated Ireland. Founded in centuries old animosities and experiences, these fears were very real for those who held them, and were manifest not by reference to Protestantism in the Ulster Covenant, but through the words that Home Rule would be ‘subversive of our civil and religious liberties’.

Confirmation of the subversive links between Catholicism and the Rebellion first became underlined with its simple timing, coming alongside the religious festival of Easter. A Christian festival for all denominations, the scheduling was indeed intended to coincide with a holiday period when it would be easier to mobilise men, but it also had a much deeper resonance for the devoutly Catholic conspirators. Some two weeks prior to the events, Papal Count George Plunkett was dispatched to Rome to seek the blessing of the then Pope Benedict XV. Plunkett later recorded the Pope as being ‘very much moved’ as he explained to him the reasons for the date of the Rebellion, and pledged the fidelity of the organisers to the Holy See and the ‘interests of religion’. After the audience the Pope conferred his ‘Apostolic Benediction on the men who were facing death for Ireland’s liberty’. Plunkett would later be Sinn Fein’s first chosen candidate for the Roscommon by-election of 1917.

Confirmation of the subversive links between Catholicism and the Rebellion first became underlined with its simple timing, coming alongside the religious festival of Easter. A Christian festival for all denominations, the scheduling was indeed intended to coincide with a holiday period when it would be easier to mobilise men, but it also had a much deeper resonance for the devoutly Catholic conspirators. Some two weeks prior to the events, Papal Count George Plunkett was dispatched to Rome to seek the blessing of the then Pope Benedict XV. Plunkett later recorded the Pope as being ‘very much moved’ as he explained to him the reasons for the date of the Rebellion, and pledged the fidelity of the organisers to the Holy See and the ‘interests of religion’. After the audience the Pope conferred his ‘Apostolic Benediction on the men who were facing death for Ireland’s liberty’. Plunkett would later be Sinn Fein’s first chosen candidate for the Roscommon by-election of 1917.

During events themselves, within the confines of the Rebellion headquarters in the General Post Office, from the outset the rosary was recited on a half hourly basis. This particular element is cited as being one of the reasons responsible for the few Protestant participants converting to Catholicism during the proceedings. In its immediate aftermath, whilst pulpits across Ireland saw priests deliver messages of condemnation, they were short lived and did not reflect the church hierarchy. Of the 31 Catholic Bishops of Ireland in 1916, only 7 actually came out to condemn the rebels. As an additional relevant aside, at the Sinn Fein convention of April 1917 ten percent of all delegates were Catholic priests.

Across the centuries, Irish Nationalist and Irish Republican leaders many times endeavored to convince the foolish non-Catholics of Ireland, that their religion and entwined social values and cultural traditions were respected, and would be protected if only they would see sense and conform to their view of Irish Nationhood. That their cause was about Nation and rights, not religion. With Easter 1916, the connection Unionism already believed there was between Irish Nationalist political ambition and Catholicism was clearly illustrated. The instantaneous establishment of the commemoration of the Rebellion remaining at Easter irrespective of the date, possibly the only non-biblical anniversary in the world that binds itself in such a way to a religious festival, permanently cemented Unionist opinion. The Rebellion and Catholicism were inextricably linked.

Across the centuries, Irish Nationalist and Irish Republican leaders many times endeavored to convince the foolish non-Catholics of Ireland, that their religion and entwined social values and cultural traditions were respected, and would be protected if only they would see sense and conform to their view of Irish Nationhood. That their cause was about Nation and rights, not religion. With Easter 1916, the connection Unionism already believed there was between Irish Nationalist political ambition and Catholicism was clearly illustrated. The instantaneous establishment of the commemoration of the Rebellion remaining at Easter irrespective of the date, possibly the only non-biblical anniversary in the world that binds itself in such a way to a religious festival, permanently cemented Unionist opinion. The Rebellion and Catholicism were inextricably linked.

A central feature of the Rebellion, arguably the most symbolic element, was the Proclamation of the Irish Republic. Within it the insurrectionists, or more accurately the documents seven co-signatory’s, declared Ireland’s Independence from the United Kingdom, and with it outlined their motivations and goals to the Country and to the world. It included an apparent olive branch, an offer to the Unionists of the North East who were so at odds with the ideals of Irish Nation. This promise to cherish all of the children of the Nation equally, came with assurances of religious and civil liberties, equal rights and equal opportunities.

By the same token, as quickly as the hand of friendship was offered it was taken away. The Proclamation demanded and claimed a full legitimate entitlement to the allegiance of every citizen within the declared Republic. Rights were offered, but solely within the definitions of conformity.

The events of the Third Home Rule crisis had illustrated very clearly that the Covenanters of Ireland were not just a religious grouping. Everything leading to and surrounding the Ulster Covenant very clearly underlined that these individuals were an ethnic grouping in their own right, with their own views of Irish history, their own ideas of collective identity. These people considered themselves Irish, but within a broader British identity. The Proclamation reduced this massive section of its ‘Nation’ to impudent fools. The Proclamation, without any recognition of the irony, included a token gesture of friendship to these misguided ‘family members’, within a manuscript that holistically was confirming they were enemies and they were now officially at war.

Prior to the events in Dublin the debate on the potential partition of Ireland had raged for several years. It was not an automatic given, but when partition was referred to specifically, Ulster Unionists initially were adamant that all nine Ulster Counties must be included in any partition solution. The stance was underlined by the monumental Ulster Covenant campaign, and many reaffirming public pronouncements. Behind the scenes however, many were beginning to waver as to the composition of any hypothetical ‘new’ Ulster.

Prior to the events in Dublin the debate on the potential partition of Ireland had raged for several years. It was not an automatic given, but when partition was referred to specifically, Ulster Unionists initially were adamant that all nine Ulster Counties must be included in any partition solution. The stance was underlined by the monumental Ulster Covenant campaign, and many reaffirming public pronouncements. Behind the scenes however, many were beginning to waver as to the composition of any hypothetical ‘new’ Ulster.

In July 1914 the Buckingham Palace conference, called by King George V to bring together Irish Unionist and Nationalist leaders, first heard the idea of a six county partition solution mooted at a level of officialdom. They broke up with no agreement, but it did result in an amended Government of Act 1914, the Third Home Rule Bill, passing Parliament with the composition of the ‘Ulster’ referenced within it left ambiguous.

The Partition of Ireland was on hold, and while discussion continued on the subject, the War effort and cause kept the issue on hold, it being seen as of much lesser importance than the events on the Western Front and elsewhere. And with that hold there still was hope within all sides that partition could be avoided. Partition was NOT inevitable. The subject was deemed to be of secondary importance and it could ‘wait’, and perhaps solutions could be found. The Rebellion changed that, and indeed changed the entire dynamic of the partition debate.

At a very superficial level the events in Dublin reaffirmed Unionist belief that Irish Nationalism was untrustworthy. In a single week Unionist predictions of revolt and subversion if stranded in an Ireland in which it was a minority, were realised. Beyond this infinitely important emotional hindrance to the idea of Home Rule within the Unionist psyche strengthened, at a practical level there were other new developments. British political relations with America were suffering as a result of events in the aftermath of the Rebellion, the Irish diaspora there having immense influence, and the Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George was determined to rectify this by forcing through an amended 1914 Government of Ireland Act to achieve greater Irish political stability. Lloyd George again raised the proposal to add the exclusion of six North Eastern Counties to the Bill; and Carson, made to believe that the option was the best within the context of the current ‘War effort’, agreed to the modification. It had to be sold to his people however, and that sale resulted in a further amendment, the addition of permanent exclusion.

At a very superficial level the events in Dublin reaffirmed Unionist belief that Irish Nationalism was untrustworthy. In a single week Unionist predictions of revolt and subversion if stranded in an Ireland in which it was a minority, were realised. Beyond this infinitely important emotional hindrance to the idea of Home Rule within the Unionist psyche strengthened, at a practical level there were other new developments. British political relations with America were suffering as a result of events in the aftermath of the Rebellion, the Irish diaspora there having immense influence, and the Minister of Munitions David Lloyd George was determined to rectify this by forcing through an amended 1914 Government of Ireland Act to achieve greater Irish political stability. Lloyd George again raised the proposal to add the exclusion of six North Eastern Counties to the Bill; and Carson, made to believe that the option was the best within the context of the current ‘War effort’, agreed to the modification. It had to be sold to his people however, and that sale resulted in a further amendment, the addition of permanent exclusion.

The Rebellion was directly responsible for the Partition of Ireland defined in legislation, and saw its permanent exclusion enshrined in that legislation; both coming alongside further entrenching of existing alienation within Unionism ensuring that no stepping back or lesser accommodation would be possible. As Patrick Buckland commented in his 1972 book ‘Irish Unionism’, referring to the revolutionaries ‘if their aim was… to prevent a moderate settlement of the Irish question, they certainly succeeded.’

It is beyond question that the events of the Easter Rebellion aftermath generated empathy and sympathy for Sinn Fein, alongside a further long term legacy of establishing for some the legitimacy of murder and terror to further political goals. The quasi-military proceedings also had many other more immediate consequences…

- The dead and wounded, inclusive of some 38 children including one just 22 months old.

- Hurt and resentment from those who were active in supporting and fighting in the Great War then in progress- the H.G. Wells coined ‘War to end War’.

- The entrenchment of sectarian battle lines in Ireland, and the reinforcement of fear of religious persecution.

- The contradictory Proclamation of the Irish Republic, simultaneously extending a hand of friendship to Irish Unionists, and yet also a declaration of war against them.

- And perhaps more fundamentally, the virtual guarantee of the previously just theoretical partition of Ireland.

The poetic, romantically christened ‘Easter Rising’ did indeed give much to Ireland.

Quincey Dougan is a Historical Consultant and freelance Journalist. Some of his work is available online at bygonedays.net

Unashamed Ulster Loyalist

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.