From Protest to Pragmatism charts the ups and downs in north-south relations as well cross-border cooperation as political capital ebbed and flowed in the Northern Ireland’s unionist government between 1959 and 1972.

From Protest to Pragmatism charts the ups and downs in north-south relations as well cross-border cooperation as political capital ebbed and flowed in the Northern Ireland’s unionist government between 1959 and 1972.

David McCann [Ed – name sounds familiar?] has worked his way through government archives in Belfast, Cork, Dublin and London, along with newspapers, Hansard, interviews and documentaries to piece together what at times feels like an all male soap opera set in Belfast and Dublin, with a long episodic story-arc that includes interdependent threads, melodramatic falling out and making up, leaders going behind their party’s backs, resignations, sackings and plenty of unpredictable disasters.

We’re quickly introduced to Brian Faulkner, who’s a dove when it comes to building relationship with his southern counterparts and opening up opportunity for co-operation. His strategy is to pitch ideas to the cabinet suggesting that they give him freedom to negotiate with Irish counterparts but leaving cabinet with a final veto. This gives him latitude while relieving the feeling of risk for less progressive colleagues.

Prime minister Terence O’Neill is no hawk, but he feels threatened by Faulkner’s positive attitude and nervously makes his cross-border overtures in private, without forewarning his ministers or briefing the press. This nervous approach results in wobbly working relationships.

The traditional narrative states that “O’Neill brought about a radical shift in policy on North-South relations”. However David argues through his research that “O’Neill was actually content to continue with Brookeborough’s policy of prioritising Political concerns over economic advantage. The shift in policy when it came was fundamentally a reaction to internal and external pressures.”

A shift away from emphasising constitutional change to economic co-operation became the new mantra in Dublin.

In 1965 we read of the Grand Master of the Orange Order welcoming the visit of the Taoiseach Seán Lemass to Belfast. Ian Paisley dissents, arguing that “O’Neill has forfeited his right to govern by meeting Lemass”.

Early cross border cooperation includes join exhibitions and promotional material by NI Tourist Board and Bord Fáilte. Reductions in tariffs for exports from the north were small and gradual – applied to very specific industries like woven carpets type valves – to the frustration of many. This seemed easier than cooperation on fishing and agriculture.

Talks about a north-south power inter-connector must have persisted for decade, with some unionists fearing that a reliance on electrical power would be a catalyst for Irish unity.

So many of the issues from this period feel familiar today. Local government reform, internal party challenges to leadership, fellow unionists sniping from the sidelines, crises over commemorations, and land deals!

Minister for Agriculture, Harry West [was sacked] after a Lands Tribunal investigated him for the purchase of land from him by Fermanagh County Council.

By 1966, the marking of the Somme and more particularly the 1916 rising were stressing relationships. At the time Conor Cruise O’Brien said:

Ulster Protestants…commemorated…the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of the Somme, when the Ulster division was cut to pieces at Thiepval Wood. From the perspective of those who commemorated these events, the commemorations in Dublin seemed a celebration of treachery.

While the main drama focuses on the Ulster Unionist and Fianna Fáil politicians and their officials, the reader gets glimpses of rising stars like Ian Paisley and John Taylor. It was interesting to discover something of the role of Home Affairs minister Brian McConnell at Stormont having met him much later in life when he was an ailing but very enthusiastic member of the House of Lords.

In 1968, the mood changes with the emergence of the NI Civil Rights Association, Austin Currie’s sit in, and violent clashes in Derry. London – Wilson and Callaghan – push for faster progress in Northern Ireland.

Wilson reminded them that the British government had shown great financial generosity towards Northern Ireland and that the slow pace of reform put this at risk.

Like all soap operas, political storylines can be seemingly recycled at fifty year intervals. There is nothing new – not even politically – under the sun!

While Faulkner seemed to be building up to be the obvious successor to O’Neill, James Chichester-Clark was Prime Minister and “friendly neighbourliness” was maintained. But just under two years later, Faulkner took over. North-South relationships markedly improved. But events intervened – Bloody Sunday and a lack of local security powers – and direct rule followed.

It is clear that north-south cooperation is a good barometer of unionist stability and party support. David quotes from News Letter editorials (and other papers) throughout the years covered by the book, attaching significance to the mood – whether appreciative of political moves or critical – and using that as a substitute for public opinion at the time. I wonder whether today’s leader writers have future historians in mind when they write their daily reflections. With today’s bigger fonts and decreased word count in newspapers, historians writing about 2015 in fifty years time may have to plough through all kinds of sources to do the same job. [Ed – they’ll have whizzy tools and robots to read blogs and tweets!]

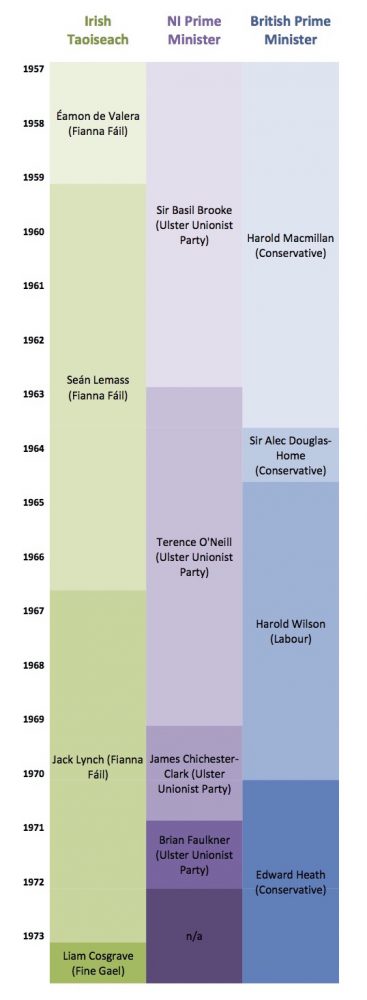

They’ll be many nuances and lessons in the text that I’ll have missed – particularly the interplay with parties outside the unionist government – and more informed political historians and observers will pick up on. I do wish David had included a table of premiers to help piece together when each premier was in power. [Ed – Here’s one I prepared earlier]

They’ll be many nuances and lessons in the text that I’ll have missed – particularly the interplay with parties outside the unionist government – and more informed political historians and observers will pick up on. I do wish David had included a table of premiers to help piece together when each premier was in power. [Ed – Here’s one I prepared earlier]

The final chapter of conclusions could be improved if it was longer and packed with more supposition – and perhaps even educated speculation and questions – based on the preceding 130 pages of timeline.

But for someone like me who didn’t live through the period and has next to no history education, From Protest to Pragmatism turned out to be a wordy yet accessible text, and provided a thorough introduction to a period of history and a set of relationships – admittedly through the eyes of governing unionists – which still resonates with much of today’s politics.

Published by Palgrave Pivot, From Protest to Pragmatism is available at suitably academic prices on Kindle (£30) and in hardback (£45).

Alan Meban. Tweets as @alaninbelfast. Blogs about cinema and theatre over at Alan in Belfast. A freelancer who writes about, reports from, live-tweets and live-streams civic, academic and political events and conferences. He delivers social media training/coaching; produces podcasts and radio programmes; is a FactCheckNI director; a member of Ofcom’s Advisory Committee for Northern Ireland; and a member of the Corrymeela Community.

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.