W

hen Ciarán Mulholland arrives at Sinnamon Coffee on Stranmillis, he is rushed, dressed in a tailored grey suit, and carrying a leather work binder. He has the firm handshake one expects from a lawyer or businessman. After apologising for running late, he steps away to the counter to order a latté. He’s not the kind of person you’d expect to be an anti-agreement republican.

Last week I received a private message on Twitter from a unionist politician who said that his party was still finalising its list of candidates for council elections. In the meantime, he said, check out Ciarán Mulholland, a human rights lawyer and an independent republican socialist from West Belfast running for city council. The two had worked together some years back and had become friends. Ciarán was recommended to me as a young, new voice in Belfast politics worth checking out.

Ciarán, 28, is the eldest of four children and grew up in the Carrigart area of Lenadoon Estate and later Andersonstown. His dad, an Irish speaker, sent Ciarán and his siblings to Bunscoil Phobal Feirste, and supported the family as a black taxi driver while his mum stayed home to care for them. Both parents returned to education later in life and remain a constant source of inspiration for Ciarán because of their strength, resilience, and ambition. Now engaged, Ciarán will be starting his own family soon.

Ciarán cares about the nitty-gritty issues affecting the most impoverished and deprived areas of Belfast. He’s angry that there are families that have to choose between eating or heating their home, and he sees Stormont and Belfast City Council as ineffectual at best.

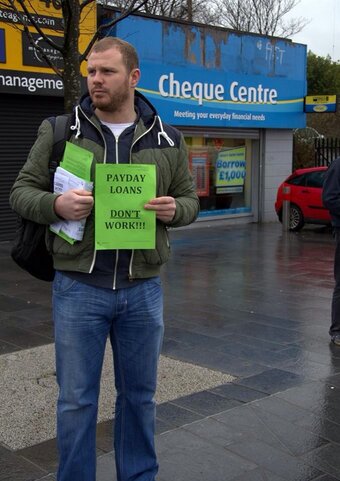

He won’t promise his constituents the moon and the stars, as he likes to say, but he will fight for them on issues such as bringing in stricter regulations on payday loan companies and arranging for further support for workers’ cooperatives. He believes in the ideal of achieving a 32-county Irish republic, but he also believes that community relations can be improved in the city by getting politicians to focus on non-tribal social and economic issues, with the regulation of payday loan companies, which he sees exploiting the city’s most vulnerable, at the top of the agenda.

As he describes his vision for local politics, I ask him why he can’t accomplish that with an established party, like Sinn Féin or the SDLP.

Neither the SDLP or Sinn Féin are delivering for the people of West Belfast, he says. The people don’t want to see another political party with more members subject to a party whip. They want independent thinking. This is why Ciarán decided to throw his hat in the ring, like a lot of republicans across the North of Ireland, and run as an independent.

Growing up in West Belfast, Sinn Féin seemed to Ciarán to be the only party to have a presence on the ground and to be offering change and improvement for ordinary people. The party stood for the kind of politics he could identify with, and as a teenager, he became an active member.

“I wanted to be a part of something new, something fresh, something innovative, because things were changing in the country, the political landscape was changing, and so I wanted to be a part of something that could change the country for the better, for the ordinary people.”

But as he grew older, and to develop his own opinions, he started becoming concerned about certain party policies and approaches. When he began asking questions, he met resistance.

Ciarán was involved with Sinn Féin on the university campus while studying in Derry. At that time, Sinn Féin was discussing the proposals of endorsing the Police Service of Northern Ireland and criminal justice system. He strongly disagreed with the party stance on policing, believing there were serious concerns that needed to be addressed before republican communities could sign up to any agreement. He was disturbed that Sinn Féin would endorse a police service where the majority of the recommendations in the Patten report would go unimplemented.

But the party’s position on the issue wasn’t, as he says, the straw that broke the camel’s back. It was the active suppression of debate and dialogue within the party that made him resign.

“Any questions or queries that were raised within the party, you were quickly told to button up. To me that wasn’t the sort of party I wanted to be in. If you’re a member of a democratic party there should always be scope for debate and dialogue.”

“To me Sinn Féin is a party run like an army. And it’s something that to a certain degree frightened me. It was a party in which you were told what to do and which way to think. And to a lesser degree it was a form of indoctrination.”

“In any democratic party, there has to be debate and dialogue and a certain degree of transparency. There has to be a place, a platform where that can be availed, and can be facilitated. Yes, I accept that certain parties are strict, and have a strong party whip, however, when you have a party where it’s frowned upon, it’s actually a culture where it doesn’t happen, you don’t ask questions. I just couldn’t be part of that.”

Ciarán explains that despite the peace process he could see no evidence of social or economic improvements in the ordinary lives of the people of West Belfast. He points to studies from Barnardos and Oxfam that detail high levels of social deprivation and poverty in Belfast and across Northern Ireland. He saw a culture in which party members and ex-political prisoners were given jobs in the community sector, but if they spoke out against the party, they faced the fear of losing their livelihood. Ciarán says this an anti-democratic form of social and financial control. “I just thought, enough is enough. I can’t be part of this any longer. And so I left Sinn Féin.”

C

iarán works in the legal profession, having completed a degree in law with Irish language at Magee college in Derry City, and a Master’s in human rights and criminal rights at Queen’s University. In addition to his day job, he serves as director of Justice Watch Ireland, which was set up to give a voice to those who wrongly fall foul of the justice system, and is heavily involved in the Justice for the Craigavon Two campaign. The campaign claims that Brendan McConville and John Paul Wootton have been wrongly imprisoned for the 2009 murder of constable Stephen Carroll.

I breach the subject of dissident republicanism with Ciarán, and when I do, I find myself saying words and phrases that I’ve heard on the radio, or in documentaries, but have never said out loud before. When I start talking I don’t know if I should try and sound more serious.

Ciarán handles my question with ease and confidence and is happy to discuss the notion of anti-agreement republicanism. Firstly, he tells me, he’s against the current armed campaign, as he fails to comprehend its logic. He doesn’t feel it will do anything to further the Irish republic. Ciarán wants peace, but more than the dysfunctional peace that’s on offer from the current political arrangements. He wants a peace based on truth, justice, accountability and transparency and political institutions with structured opposition.

“The Good Friday Agreement, and the agreements thereafter, facilitate further unionist concessions,” he says. Therefore, what is needed, is a democratic approach that encompasses the wishes of the entire island, which is why Ciarán would like to see a one Island, one vote referendum.

Many republicans, while anti-agreement, he explains, remain committed to achieving their goals peacefully through a democratic process, but get labeled as dissidents and smeared by the press and Sinn Féin when they voice their discontent.

Ciarán embraces the term dissident. In a piece written for The Pensive Quill, a republican blog edited by former IRA prisoner, Anthony McIntyre, he says, “A ‘Dissident’ is perceived by the majority of the people in Ireland as something negative, dark and dirty, and many generally have a mental picture of a warmongering Neanderthal dragging their knuckles along the ground with nothing to offer society.”

Ciarán embraces the term dissident. In a piece written for The Pensive Quill, a republican blog edited by former IRA prisoner, Anthony McIntyre, he says, “A ‘Dissident’ is perceived by the majority of the people in Ireland as something negative, dark and dirty, and many generally have a mental picture of a warmongering Neanderthal dragging their knuckles along the ground with nothing to offer society.”

He points to the dictionary definition of dissident to reframe what it means to be an anti-Sinn Féin and anti-agreement republican. A dissident, he quotes, “is a person who opposes official policy, especially that of an authoritarian state.” Ciarán says he dissents from authoritarian politics, but that he is not a dissident in the way that the word is being used in current parlance.

“I’m a republican, and I’m a socialist republican. And a republican in the sense that I want a country that is free from a monarch. I want to see the unification of the country. I want the country based on 32-county republican socialist principles, where all the children of Ireland are cherished equally. And to decide their own destiny free from state interference.”

I write about faith, democracy and culture from a Christian and centre-left perspective.

Discover more from Slugger O'Toole

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.